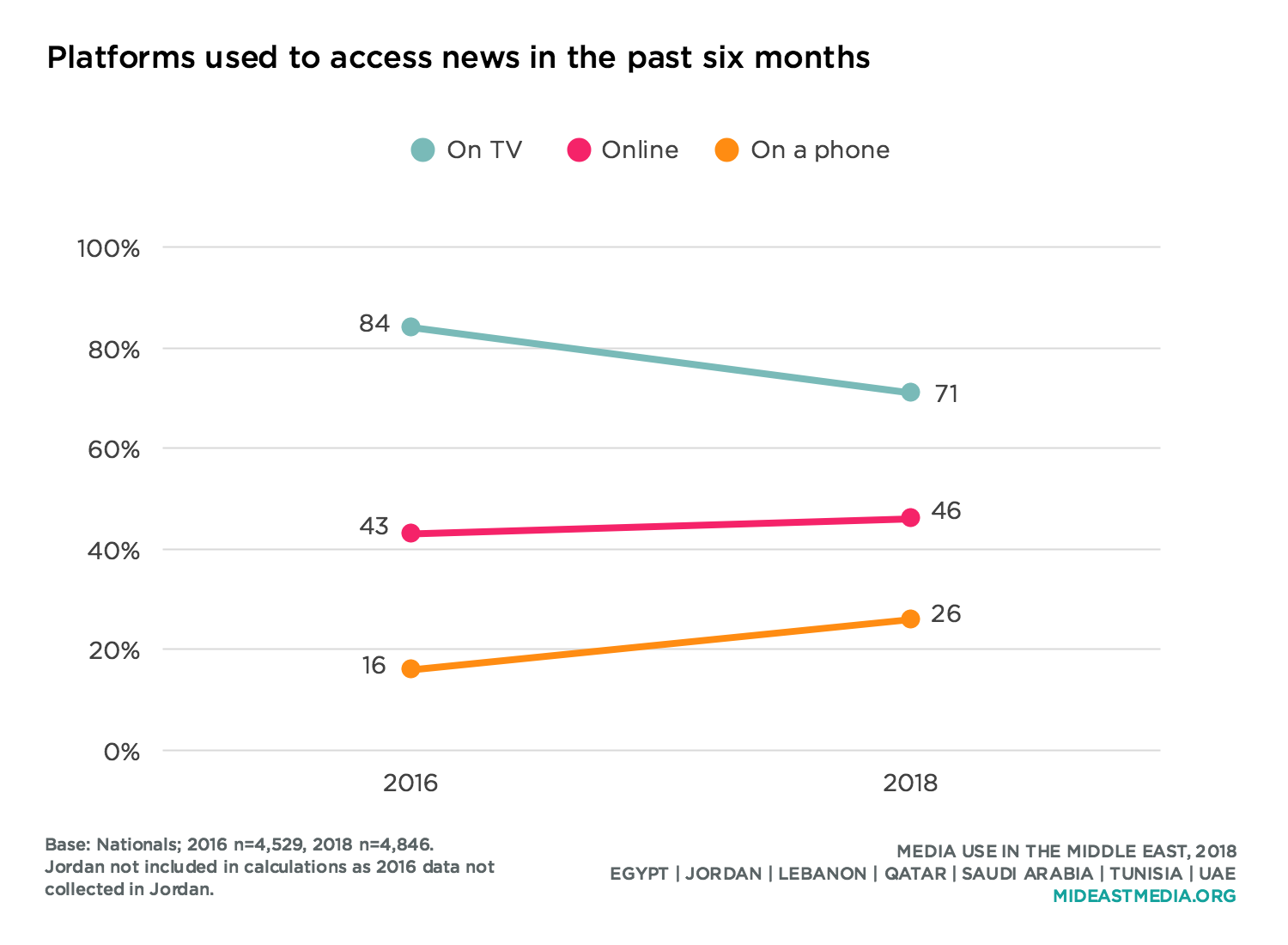

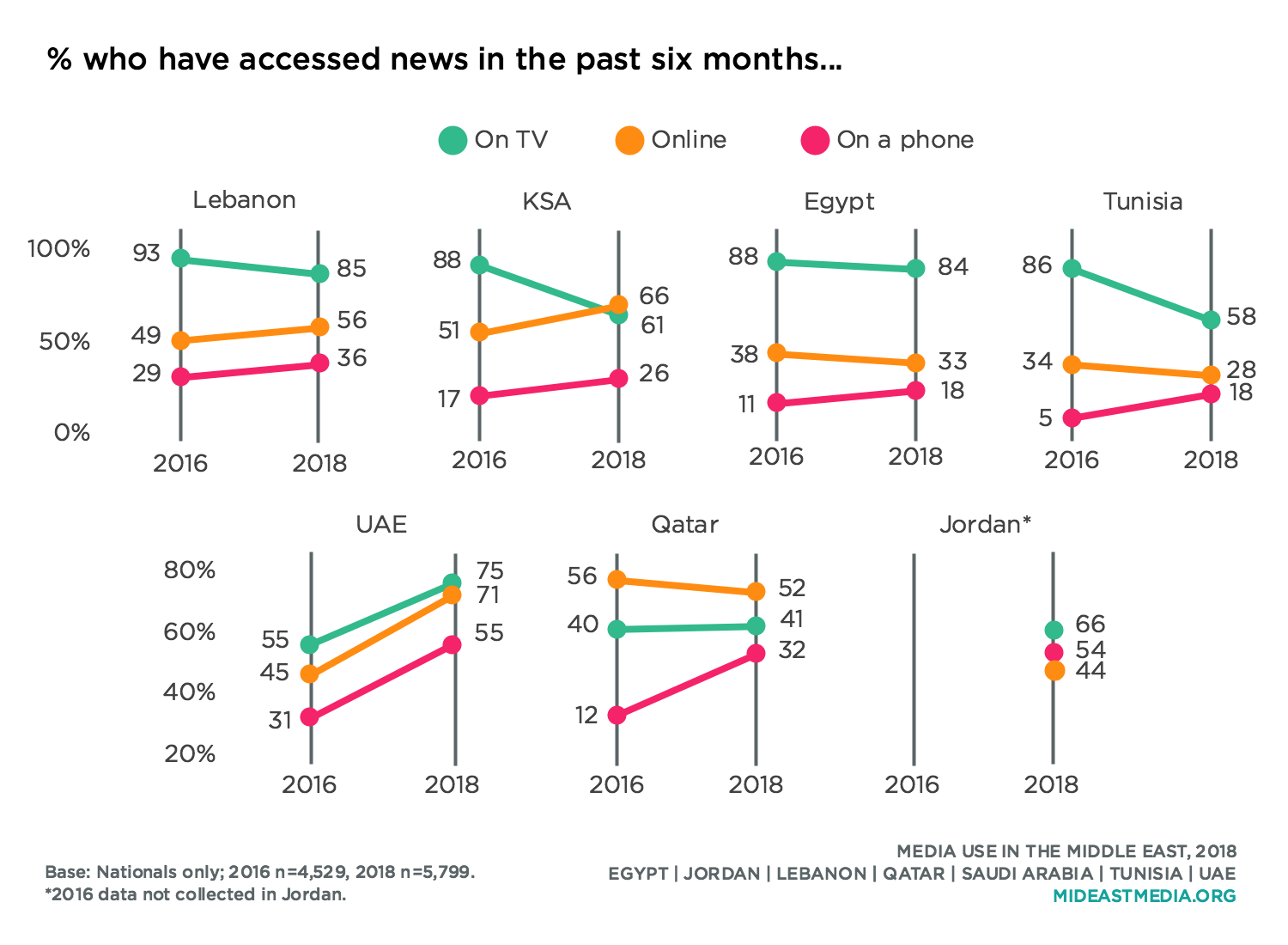

TV remains the most common source for news, but the proportion of nationals who watched news on TV in the past six months declined sharply since 2016, while the proportion who accessed news on a phone increased. In Saudi Arabia and Qatar, more nationals got news online than on TV in the past six months. Phones are increasingly used to access news in all surveyed countries.

The youngest nationals (18-24) are roughly equally likely to have used TV and the internet to access news in the past six months (59% and 52%, respectively), while the oldest nationals (45+) are more than twice as likely to have gotten news on TV as online (80% and 29%) in the same time period. Interestingly, perhaps, there is little difference between across age cohorts in the percentage that accessed news on a phone in the past six months (33% 18-24, 36% 25-43, 31% 35-44, 25%).

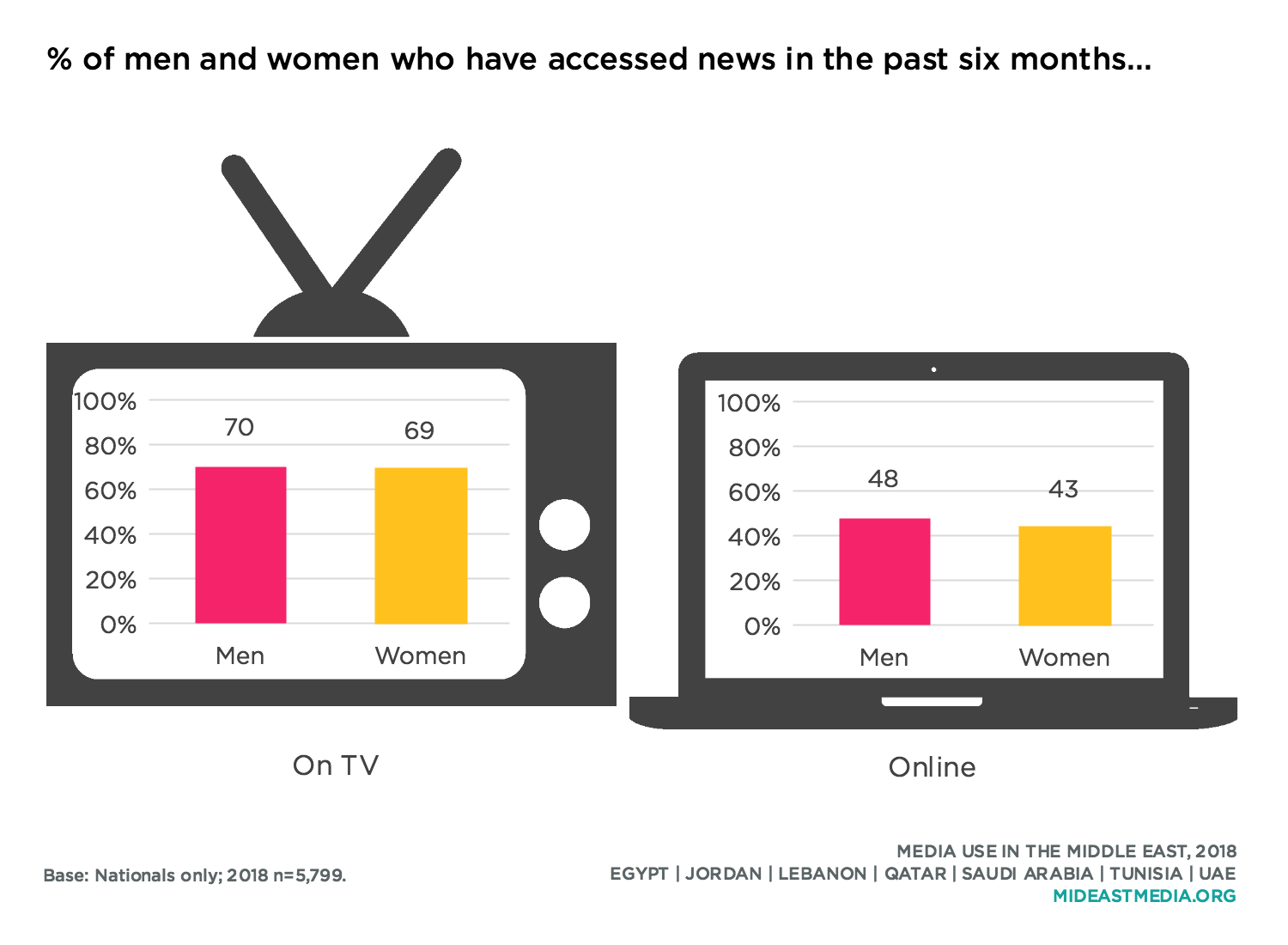

Men and women access news at similar rates both on TV and online; two-thirds of both men and women accessed news on TV, and nearly half of each group accessed news online in the previous six months.

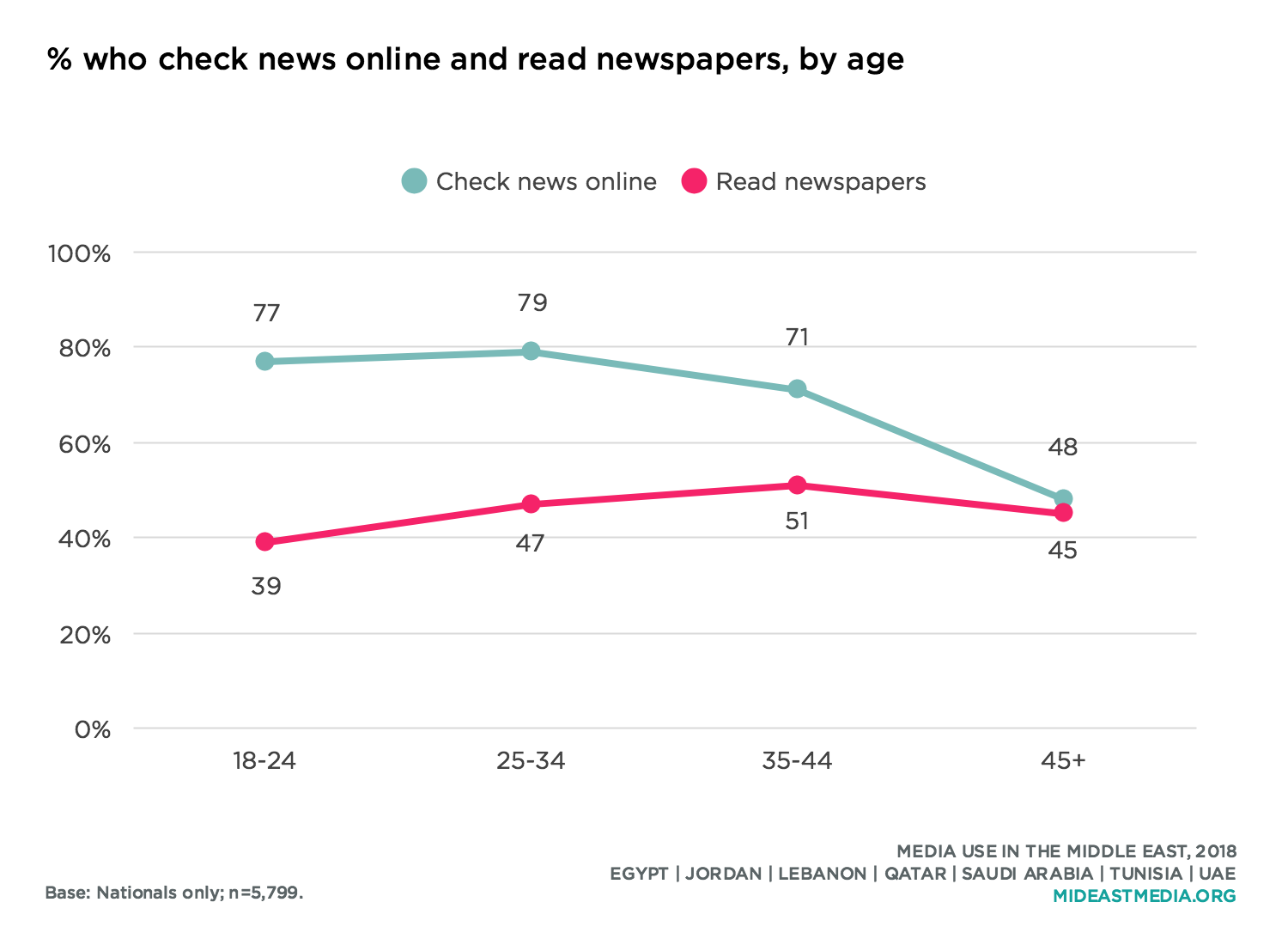

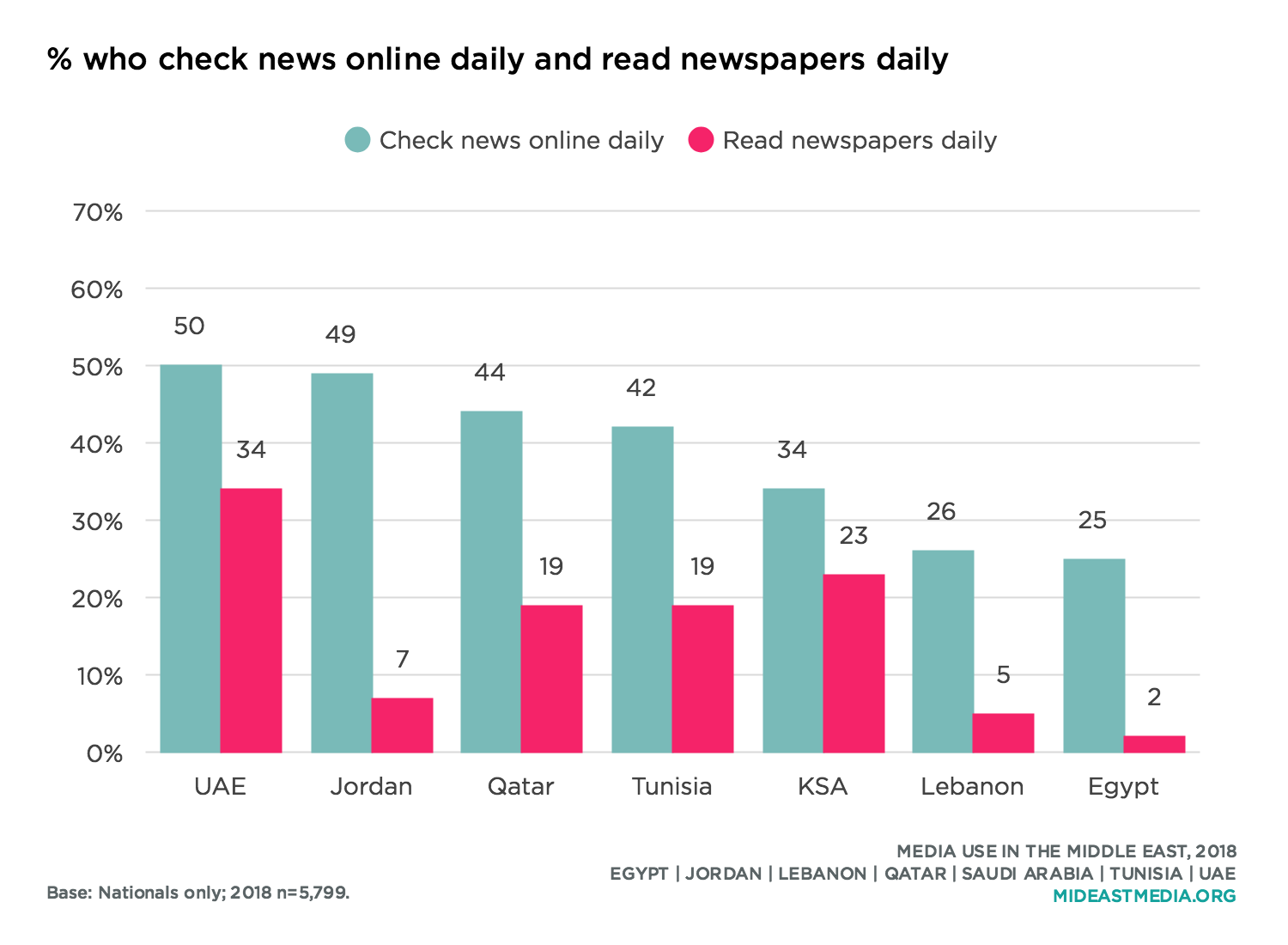

On average, seven in 10 Arab nationals get news online at all, compared to fewer than half who read newspapers.

Nationals under 25 years old report significantly higher rates of checking news online compared to those 45 and older, while the latter read news online and in newspapers at roughly similar rates (read newspapers 39% 18-24 year-olds vs. 45% 45+ year-olds; check news online 77% 18-24 year-olds vs. 48% 45+ year-olds).

Arab nationals are twice as likely to check news online every day as they are to read a newspaper every day. Daily use of both platforms for news is highest in the UAE and lowest in Egypt and Lebanon. No more than one-third of nationals in any country reads newspapers daily.

While seven in 10 Arab nationals get news online, less than 5% paid to access news online in the whole of the previous year, ranging from 5% in Lebanon and Saudi Arabia to only 1-2% in Jordan, Qatar, and the UAE. This pattern holds across key demographic groups; no more than 5% of any gender, age, or education group paid for online news in the previous year.

While nationals are turning to the internet more for news, they watch more entertainment video than news video online. Qataris are the only nationals who report watching more news online than entertainment video, a pattern consistent among Qataris since 2014.

.png)

When viewing video content online, older nationals favor news video, while younger nationals favor entertainment video (18-24 year-olds: 52% entertainment vs. 34% news: 25-34 year-olds: 46% entertainment vs. 40% news; 35-44 year-olds: 45% entertainment vs. 44% news; 45+ year-olds: 40% entertainment vs. 46% news).

News remains one of the top three favorite genres of TV and online video, behind only comedy. However, fewer nationals cite news as a favorite TV genre than did in 2014 (39% in 2014 vs. 30% in 2018), while news as a favorite online video genre increased in the same time period (14% in 2014 vs. 23% in 2018).

News is more frequently listed as a favorite TV genre among older nationals; nearly half of nationals in the oldest cohort cite news among their favorite TV genres (19% 18-24 year-olds, 30% 25-34 year-olds, 36% 35-44 year-olds, 45% 45+ year-olds). Preference for news as a favorite online genre does not differ much across age groups, but is still lowest within the youngest age group (19% 18-24 year-olds, 27% 25-34 year-olds, 33% 35-44 year-olds, 24% 45+ year-olds).

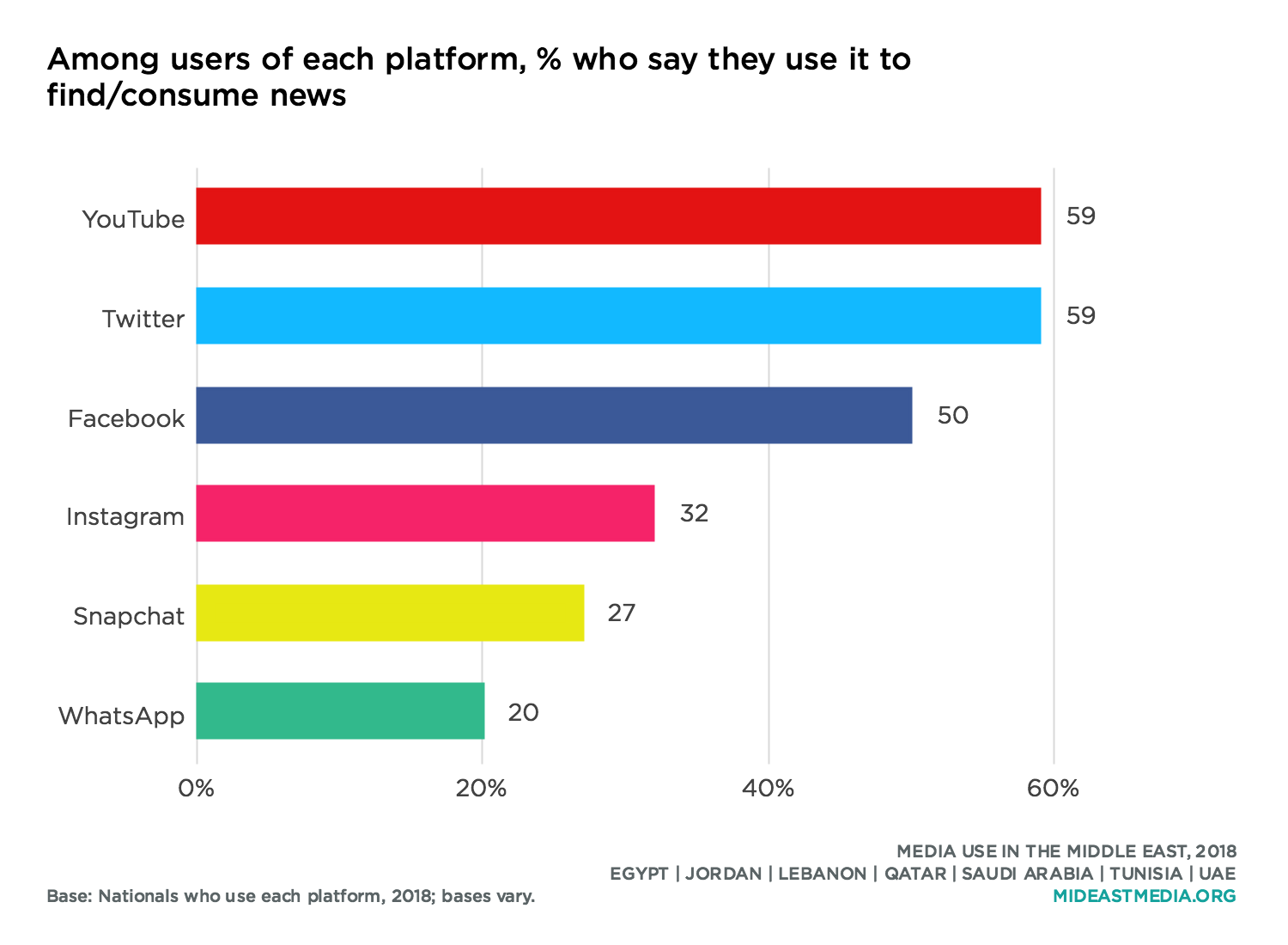

More users of YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook than users of other platforms find and consume news on those platforms. Half or more nationals use each platform to find or consume news. About a quarter or more of nationals also find or consume news through Instagram and Snapchat.

The portion of Arab nationals who have posted online comments about news or news items in the previous month grew in every country since 2014, with the most significant gains in Qatar and the UAE (by 21 and 20 percentage points, respectively).

.png)

Posting online about news varies little by age, and the youngest and oldest groups are the least likely to have posted about news in the past month (17% 18-24 year-olds, 22% 25-34 year-olds, 23% 35-44 year-olds, 17% 45+ year-olds).

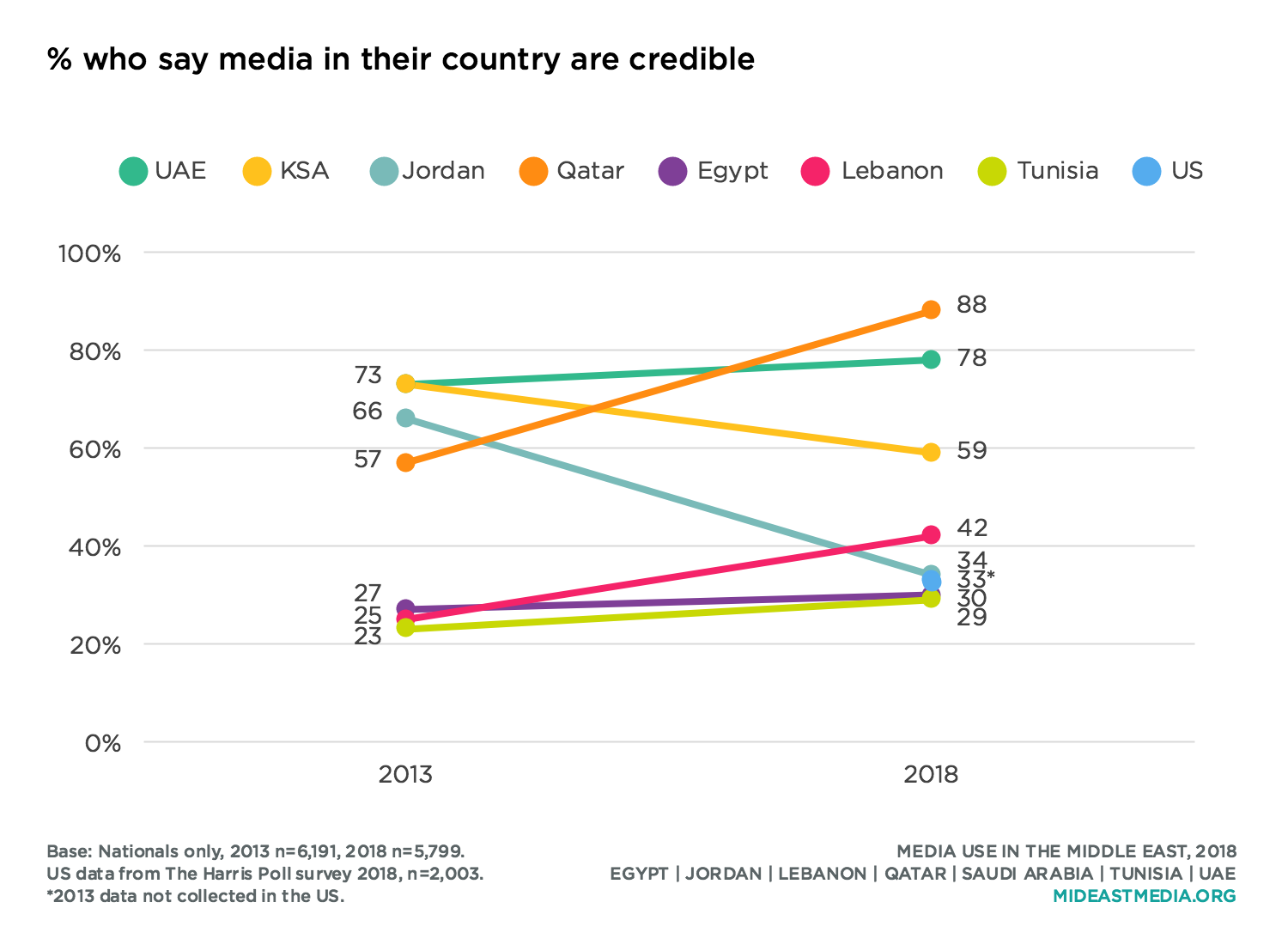

Nationals’ perceptions of news media credibility in their country varies widely across nations. Qataris are the most likely to say news media in their country are credible—nearly nine in 10 do—a 26 percentage-point increase between 2017 and 2018. Data in Qatar in 2017 were collected before the Saudi-led blockade of the country began, and it could be that following the blockade, in 2018 at least, some Qataris felt either inclined or compelled to express support for the country’s news organizations. Far fewer Jordanians in 2018, though, say news media in Jordan are credible than said so in 2013, a 32-point decrease in that period.

A large majority of Emiratis say news media in their country are credible, a figure which has changed little year to year, while far fewer Egyptians, Jordanians, and Tunisians than other nationals see their country’s news media as credible. One-third of Americans say news media in the U.S. are credible, similar to the shares of Jordanians, Egyptians, and Tunisians who say the same, though well below Qataris, Emiratis, and Saudis.

More nationals with a high school education or more say news media in their country are credible than do less educated nationals (36% primary or less, 40% intermediate, 43% secondary, 44% university or higher). Additionally, those who say their country is heading in the right direction are much more likely to view their country’s news media as credible than those who say the country is on the wrong track (65% vs. 35%, respectively).

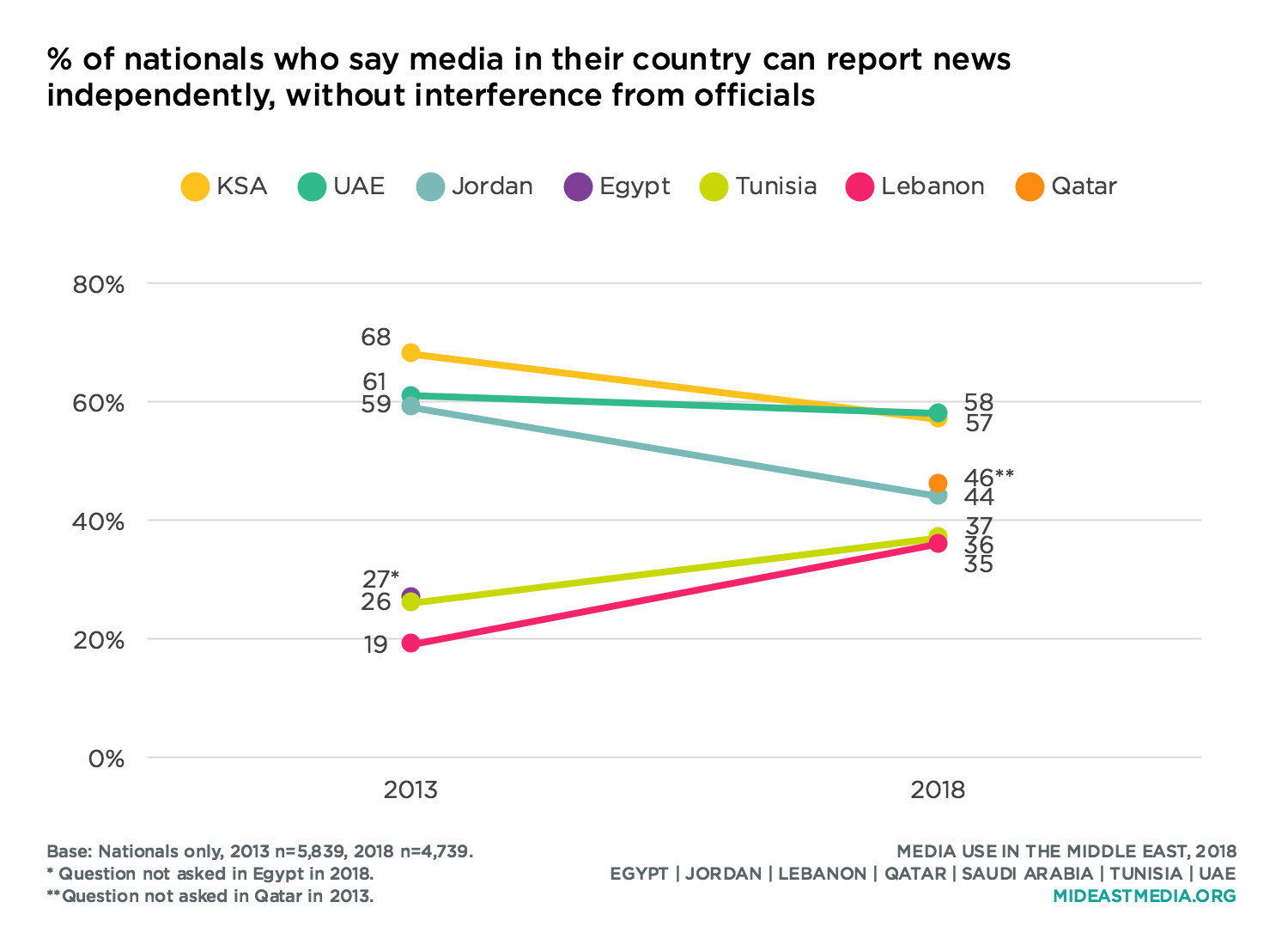

There is less variance among nationals about whether news media in their country can report news independently without interference from officials than there is regarding overall news media credibility. Most Saudis and Emiratis say media in their country enjoy this kind of independence (despite a decline for this figure in Saudi Arabia since 2013), while fewer Lebanese and Tunisians say media in their country can report without official interference. Nearly half of Qataris say news media in their country can report news without interference from officials.

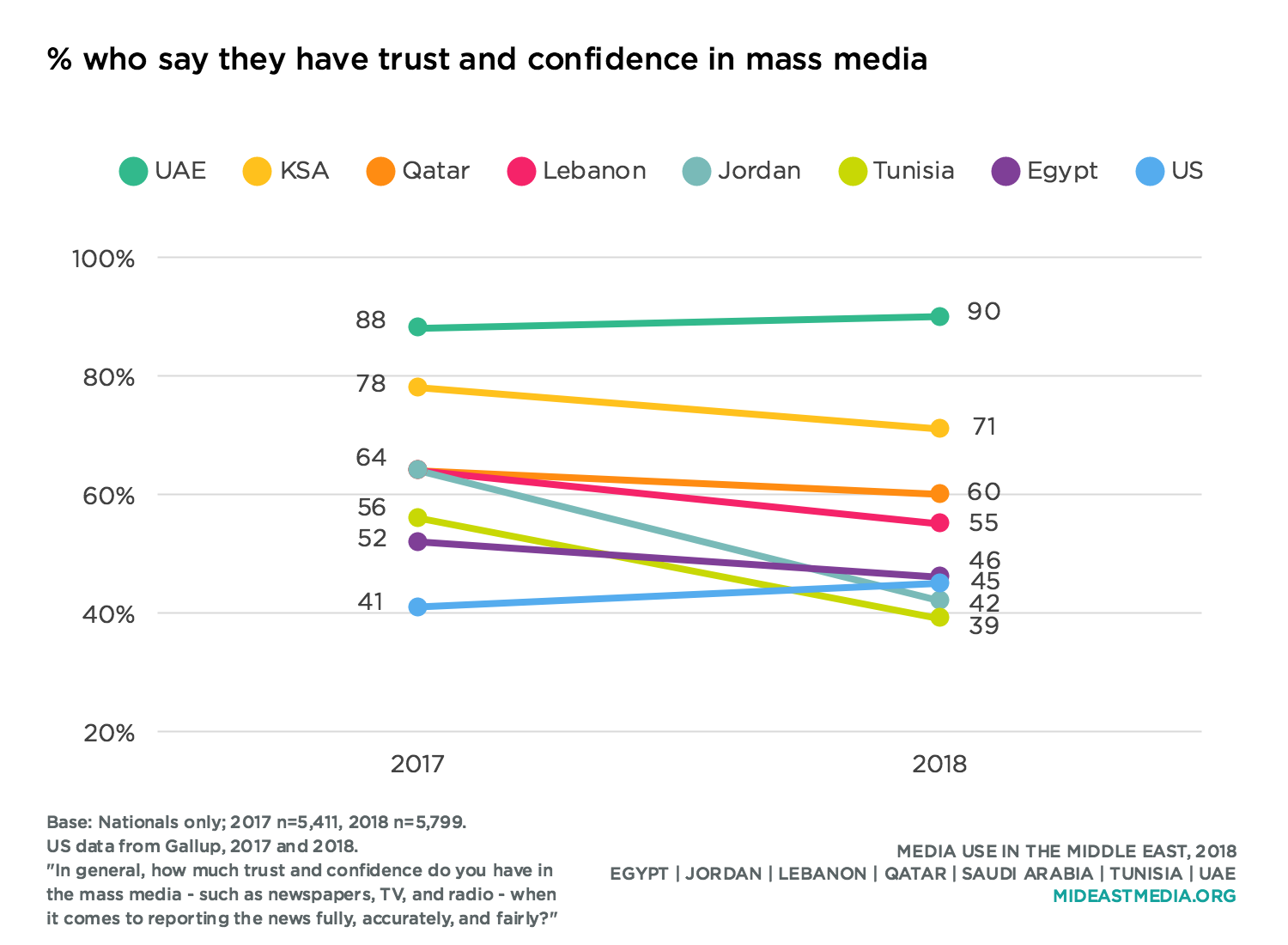

Trust in mass media to report the news fully, accurately, and fairly—the decades-old Gallup polling item replicated in this study—declined in the past year in every country except the UAE, where rates of trust in media are, and where they remain, the highest in the region. Trust in mass media in Arab most countries in this study is falling, while from 2017 to 2018 the share of Americans who trust mass media increased modestly, from 41% to 45%.

Trust in the mass media is more common among self-described cultural conservatives than progressives (57% vs. 43%, respectively), and is more common among nationals who say their country is moving in the right direction compared to those who say it is on the wrong track (76% vs. 41%, respectively).

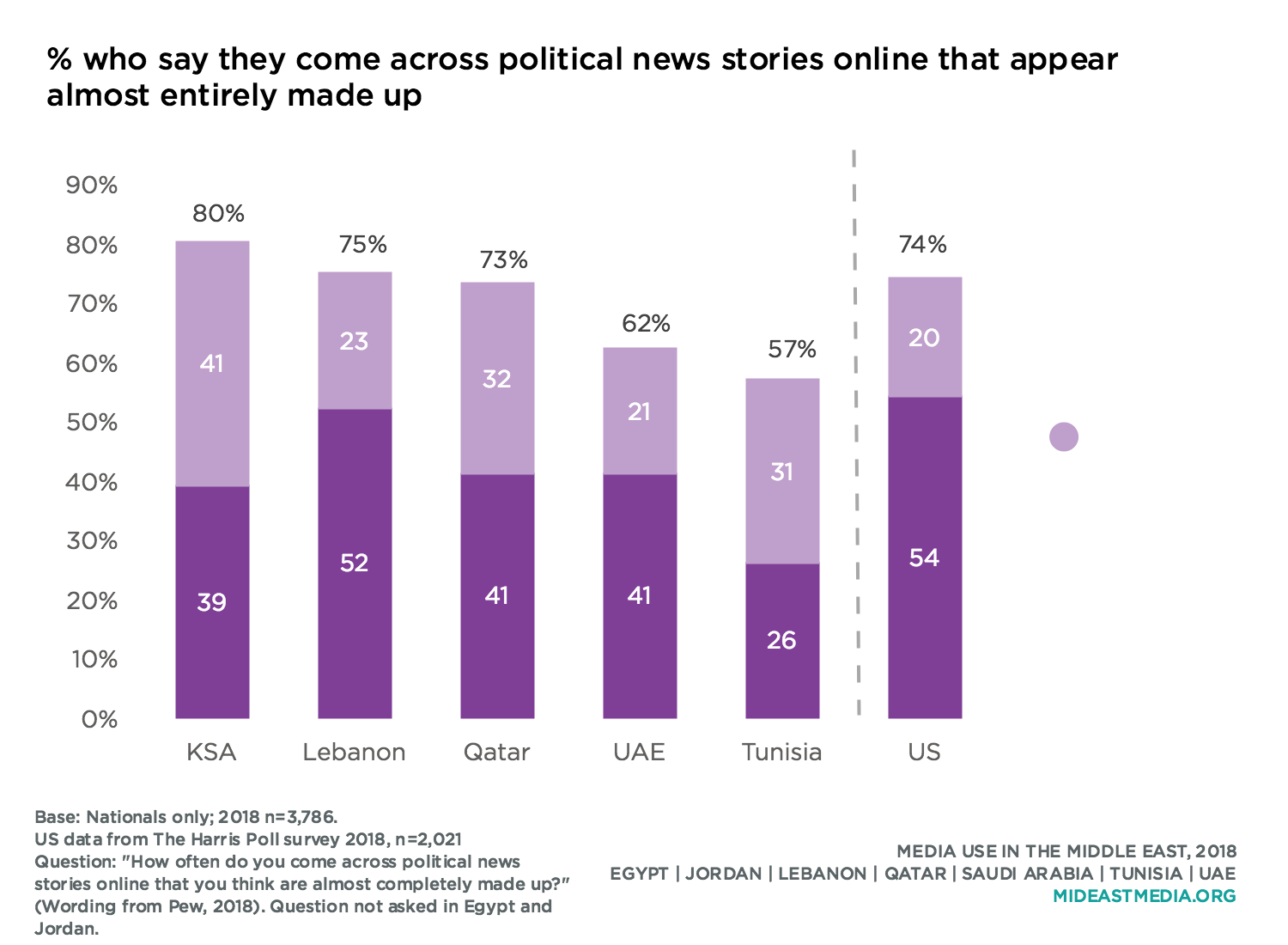

More than half of Arab nationals in all countries surveyed say they come across political news stories online they think are almost completely fake (either sometimes or often). Three-quarters of Qataris, Lebanese, and Saudis say they come across patently false news items sometimes or often—similar to the percentage of U.S. nationals who say the same.

The share of respondents who say some political news items they see online are fake increases with education, but majorities of nationals across all education levels say they come across fabricated news online sometimes or often (56% primary or les, 69% intermediate, 70% secondary, 73% university or higher). Cultural conservatives are somewhat more likely than progressives to say they have come across completely made up political news stories online (73% vs. 66%, respectively).

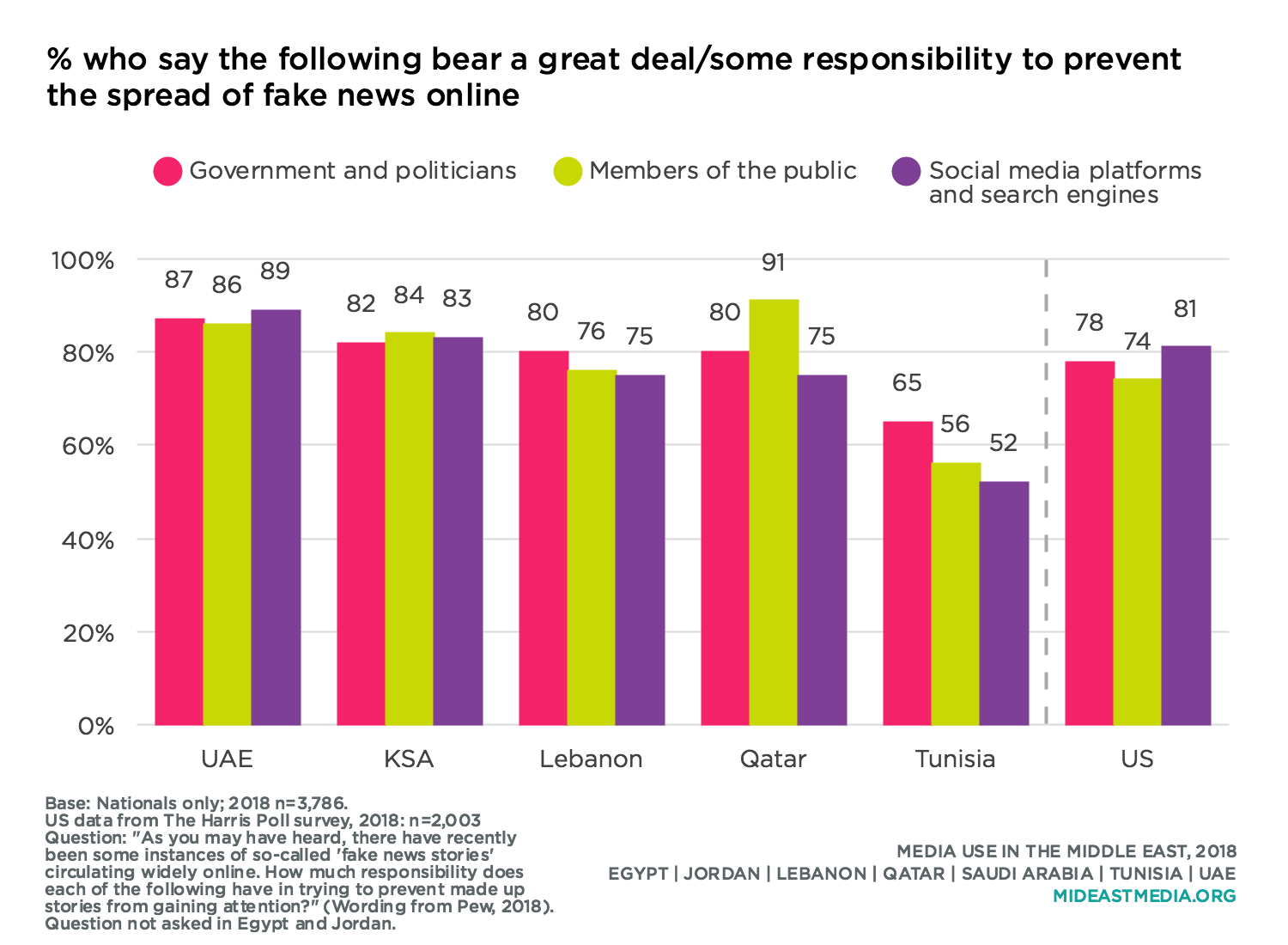

Significant majorities of Arab nationals in all countries under study say preventing fake news from gaining attention online is at least partly the responsibility of government, the public, and social networking sites. Americans agree, but slightly more Americans say social media platforms and government, as opposed to the public, bear responsibility for stopping the spread of fake news. Questions about fake news were not permitted by officials in Egypt or Jordan.

A hybrid, interdependent, and political landscape: The news is bad, but still important

Fatima el Issawi, University of Essex

Arab audiences don’t have to choose between platforms to access information. They enjoy a panoply of choices, and they are making use of them in a relational, interdependent, yet competitive manner. The findings of the new survey of media usage in the Middle East confirm the hybridity of these practices while reflecting a landscape in tune with international trends. While television remains the main provider of news for Arab audiences, with very high rates of consumption, there is a steady consolidation of the habits of accessing news online. Meanwhile, the phone is confirming its role as the favorite and most practical, personal, and cozy tool to get informed, across all ages.

These findings corroborate Andrew Chadwick’s seminal analysis on the hybrid media system, where political communication is relational by nature and power is understood “as the use of resources of varying kinds that in any given context of dependence and interdependence to enable individuals or collectivities to pursue their values and interests, both with and within different but interrelated media” (2013:207). In a departure from the excessive focus on social media uses and its effects on the Arab public sphere within the context of Arab uprisings, this survey’s findings reflect a mitigated landscape where audiences construct their world by simultaneously using different platforms to get informed, to check information and to negotiate, accept, or reject it. In this new hybrid media ecology, the wide diversity of media use as shown in the survey’s findings confirms international trends towards “a balance between the older logics of transmission and reception and the newer logics of circulation, recirculation and negotiation” (Chadwick, 2013:208). While the access to news through social media and the phone is growing steadily simultaneously with the decline of newspapers’ readership and radio’s audiences, the survey does not give indications on the original source of the news accessed through new media platforms: is this a circulation or re-circulation of press articles, op-eds, or other news material produced by the legacy media, thus re-confirming the continuous prominent role of traditional media as the main provider of information?

The Arab public sphere, as demonstrated by this survey, is dynamic and diverse, departing from expectations of a rather dormant or fearful sphere as a result of the raging counter-revolutions in the region, accompanied by vicious pressures and limitations used to suppress dissent. While media consumption rates are high, one can notice a complex relationship of love-hate between audiences and their national media, thus confirming the intricate link between media and politics and defying the analysis that sees traditional media as a simple tool for politics in hybrid-authoritarian contexts.

It is not a surprise to see the lowest rates of trust in media in Tunisia, a country that represents a successful yet very fragile model of democratic consolidation while scoring high in recent international rankings (69 in Freedom House ranking of freedoms in the world for the year 2019, the only Arab state ranked as free) along with a slight increase in the belief in media’s independence. A similar landscape can be seen in Lebanon and Jordan where, like in Tunisia, the public debate is open to a certain extent while increasingly suffering new repressions. The public attitude of suspicion towards national media in countries where levels of media freedoms are higher attests to an awareness of the political influence of media and a willingness by the civil society to monitor its activities without going to the extent of rejecting it or denying its important role. On the contrary, a remarkably high rate of trust and confidence in national media’s independence is observed in most Gulf countries where the public debate is much more restricted. This trusting attitude can be explained by the rise of nationalism in politics and media amid a tough diplomatic crisis, unprecedented in the history of the Gulf region, in which national media played a major role as a platform for political communication, fully engaged in the battle of conflicting narratives. It is quite significant to see that most Saudi and Emiratis surveyed believe their national media enjoy independence from political interference, while national media in the two countries were seriously engaged in spreading misinformation on the brutal killing of Saudi critical journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

News is bad, but this did not stop the public from actively seeking to be informed or commenting on news online—for instance, a balanced interest in news and entertainment is seen in Tunisia and Jordan while the imbalance in profit for entertainment remains noticeable in Egypt but without deterring the public from following the news. Countering expectations for a decline in the Arab public’s appetite for debates within an international climate of mistrust in news, widespread misinformation, and an unprecedented level of suppression of dissent amid growing nationalistic trends, patterns of media consumptions as shown in this survey remain deeply political.