Large majorities of Arab nationals in each country, except Tunisia—about three-quarters or more of other nationals—believe entertainment media in the Arab region should be more tightly regulated for both violent and romantic content. But still a sizable minority of Tunisians—four in 10—agrees.

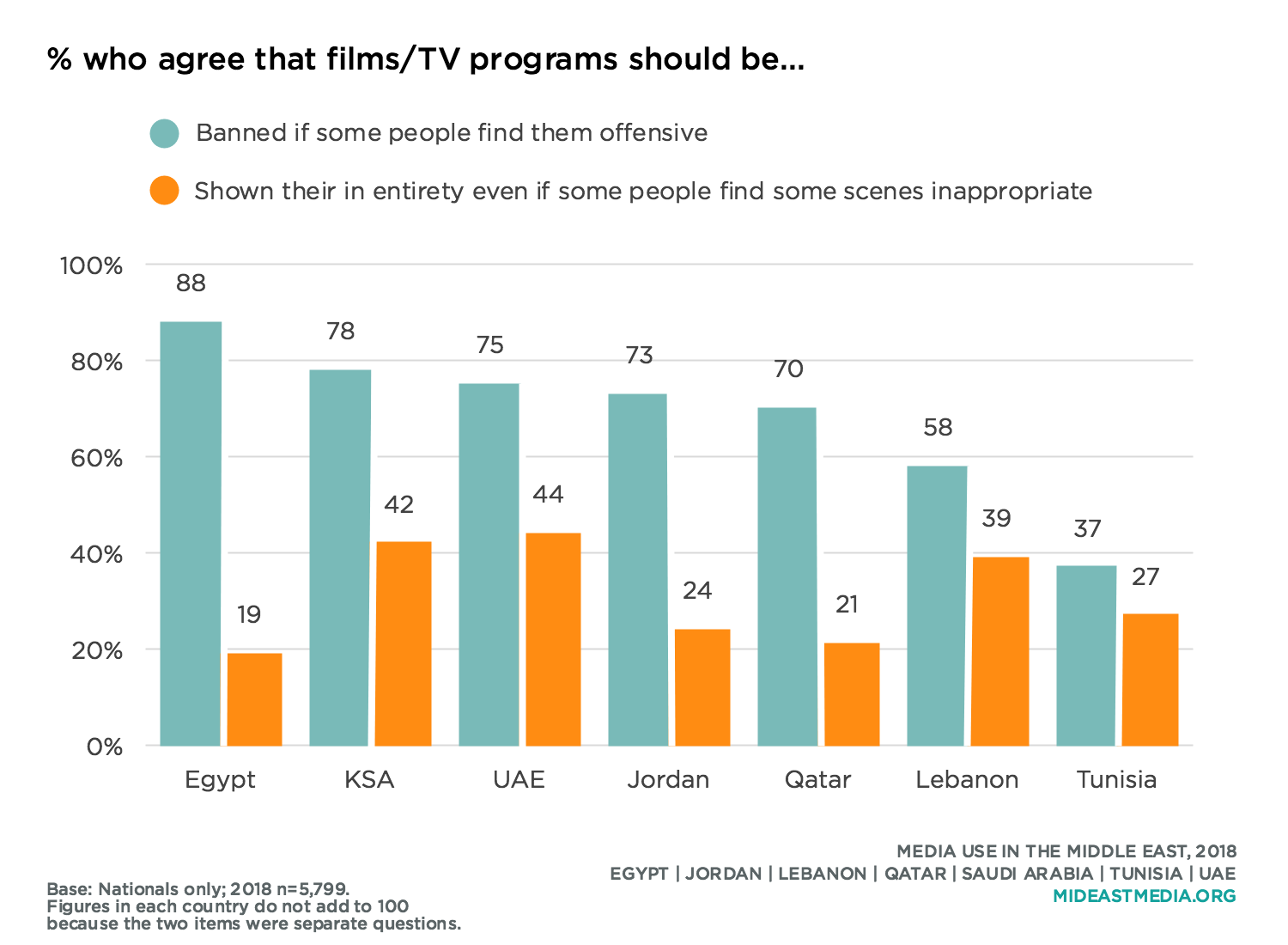

Similar proportions of nationals also say films or TV programs other people find offensive should be banned—at least 70% of Saudis, Emiratis, Egyptians, Jordanians, and Qataris, and nearly as many Lebanese, support such bans. Likewise, only a minority of nationals say films or TV programs should be shown in their entirety even if some people find them offensive. No more than roughly four in 10 Saudis, Emiratis, and Lebanese, and only about a quarter of Jordanians, Qataris, and Tunisians—and even fewer Egyptians—say potentially offensive content should remain available to the public.

However, there has been a small decline since 2014 in the share of nationals that supports banning some films or TV programs, and a modest increase in the proportion that supports showing entertainment in its entirety even if it has potential to offend (films or TV should be banned if offensive: 70% in 2014 vs. 65% in 2018; show entertainment in entirety even if offensive: 27% in 2014 vs. 31% in 2018).

Culturally conservative nationals are more likely to favor censorship than are their progressive counterparts—about seven in 10; still, about half of progressives also advocate tighter regulation of violent and romantic content as well as support deleting scenes or banning programs seen by some people as offensive.

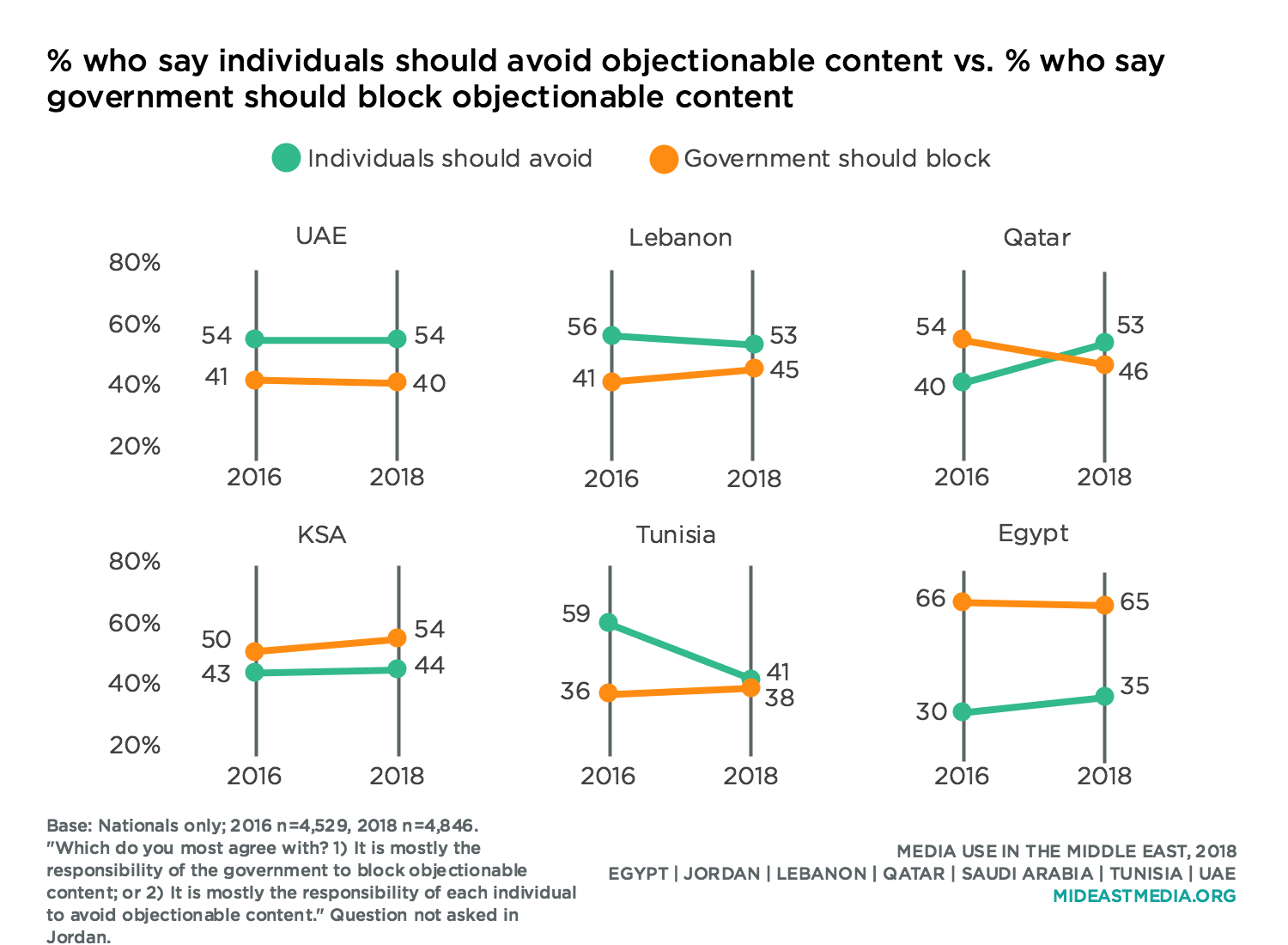

There is no clear consensus on who should be responsible for regulating objectionable media content, individuals themselves or governments. More nationals in most countries say it is mostly the responsibility of individuals to avoid objectionable media content, rather than the government’s responsibility to block objectionable content, though by modest margins. Only in Egypt and Saudi Arabia do more nationals say governments bear responsibility to regulate potentially offensive content than say individuals should make such decisions themselves.

Most nationals with children in the household—three-fourths or more, except Tunisia—want the government to do more to protect children from potentially offensive entertainment content (93% Egypt, 81% Qatar, 80% KSA, 80% UAE, 73% Lebanon, 43% Tunisia).

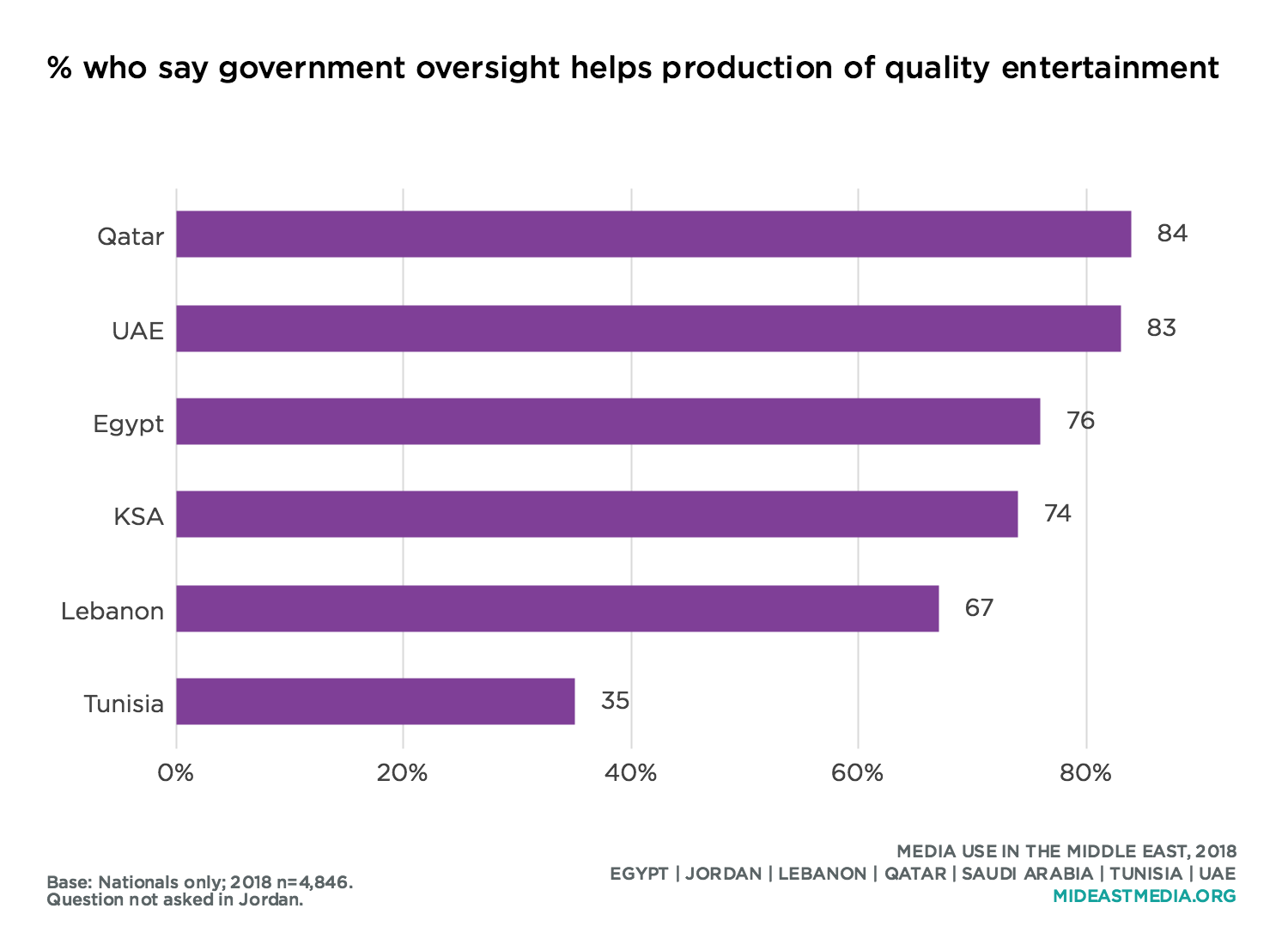

The vast majority of Arab nationals say government oversight bolsters the quality of entertainment content; at least two-thirds of nationals in every country (except Tunisia) express this belief, especially Egyptians, Qataris, and Emiratis.

Two-thirds or more of nationals in most countries, and four in 10 in Tunisia, say it’s OK for entertainment content to portray problems in society.

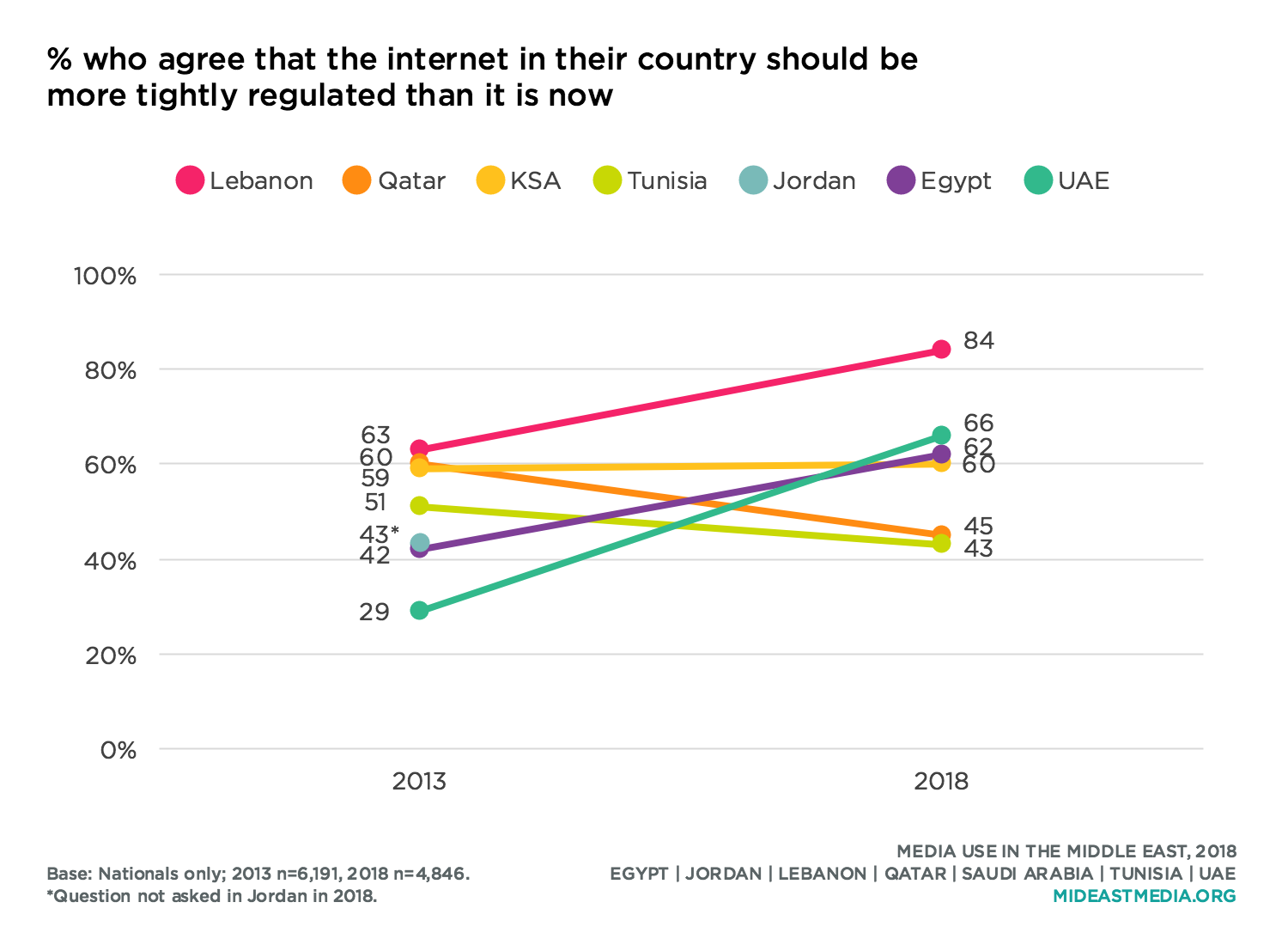

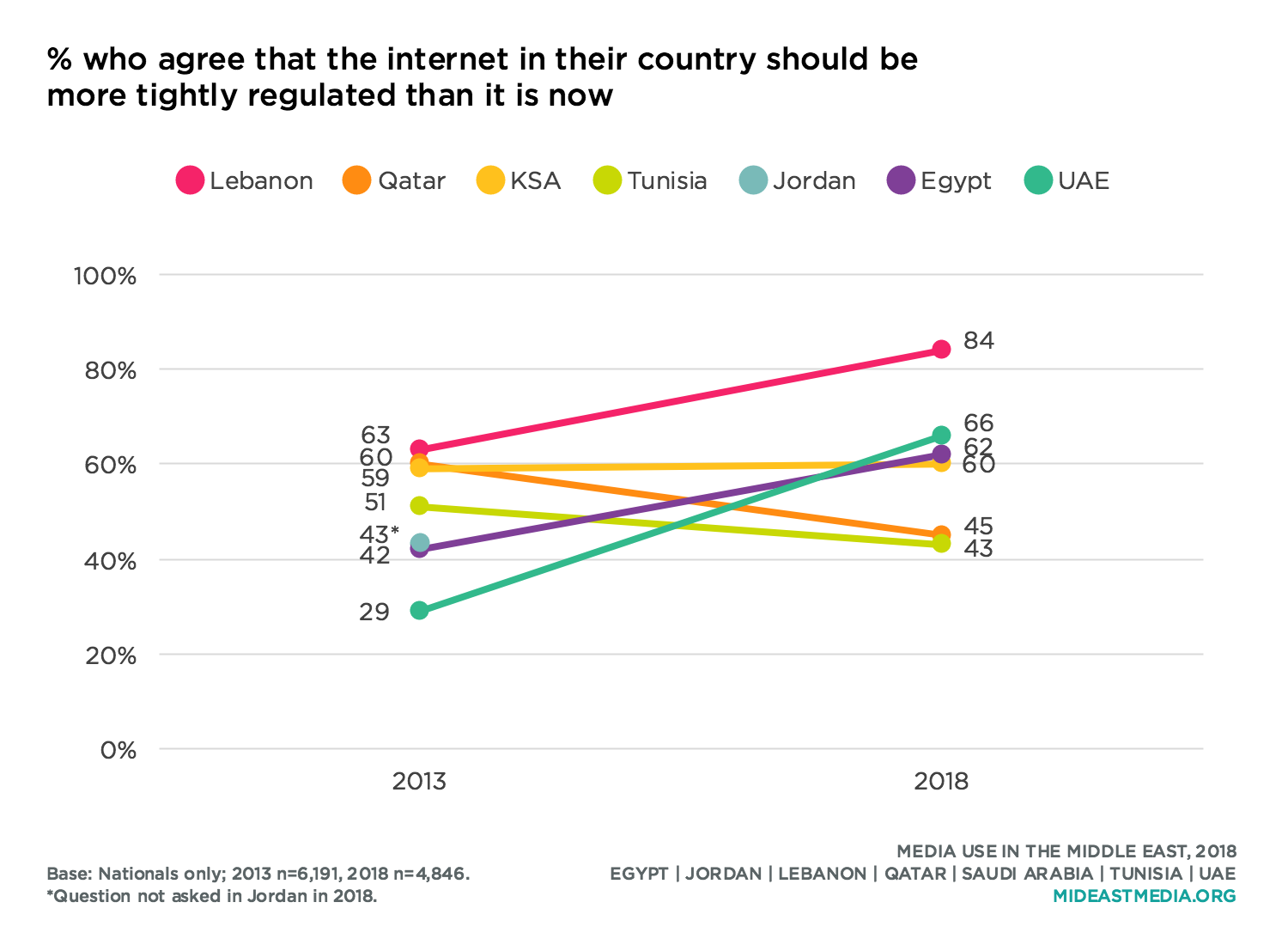

Clear majorities of nationals in four countries—Egypt, Lebanon, UAE, and Saudi Arabia—want more internet regulation in their countries, while just over four in 10 Qataris and Tunisians also support greater internet regulation.

In Media Use in the Middle East, 2017, respondents in the same countries surveyed here who said they wanted more internet regulation were then asked what kind of regulation they favored. Six in 10 nationals said they wanted more internet regulation for privacy protections, while less than half said they wanted online political content to be more regulated (47%). Large numbers of respondents in several countries also said they wanted the internet more regulated in their country in order to make it affordable (in Lebanon one gigabyte of mobile data costs around $40 USD). To many respondents in that year’s survey, then, internet regulation meant providing more access to the internet, not less.

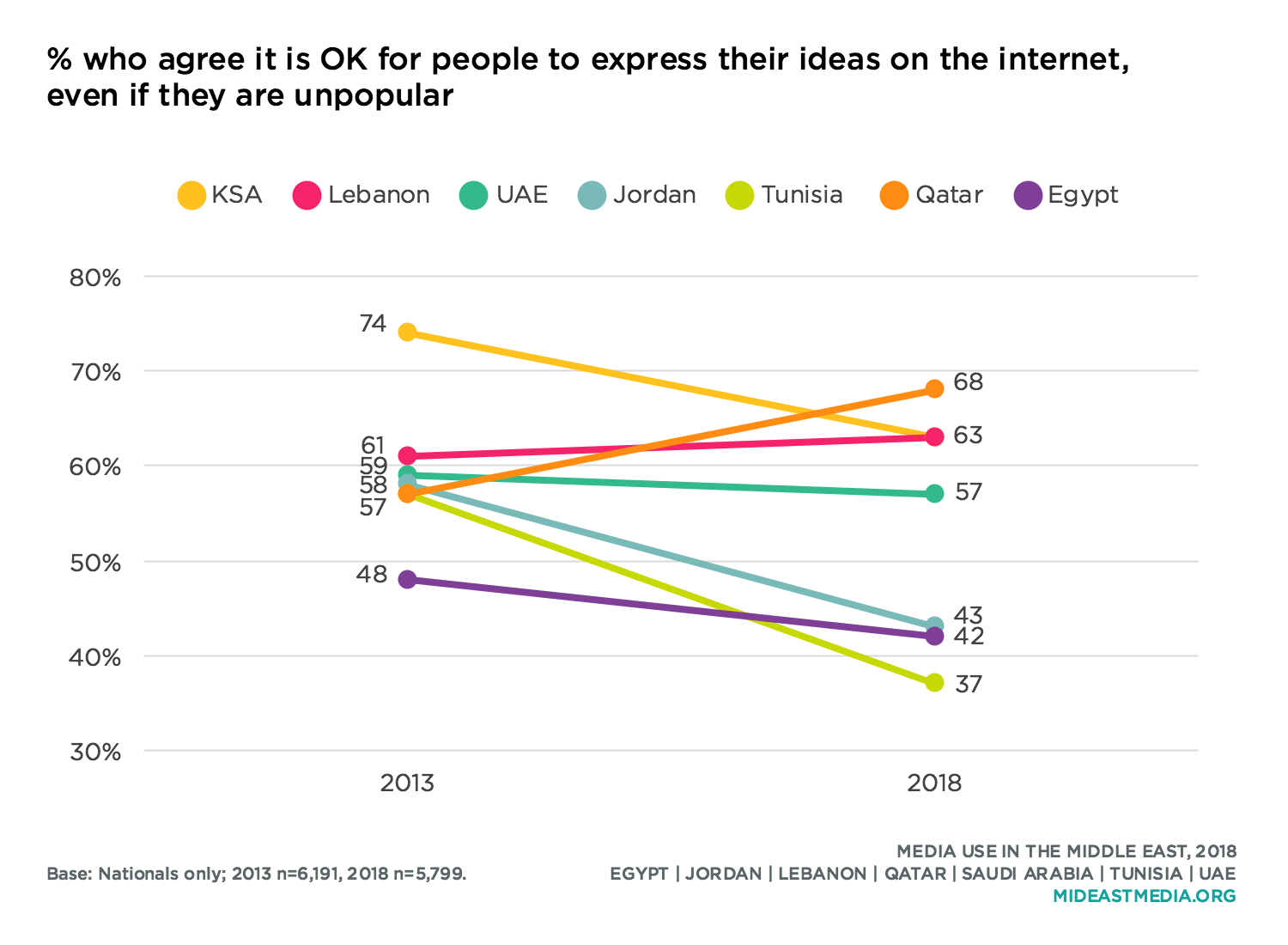

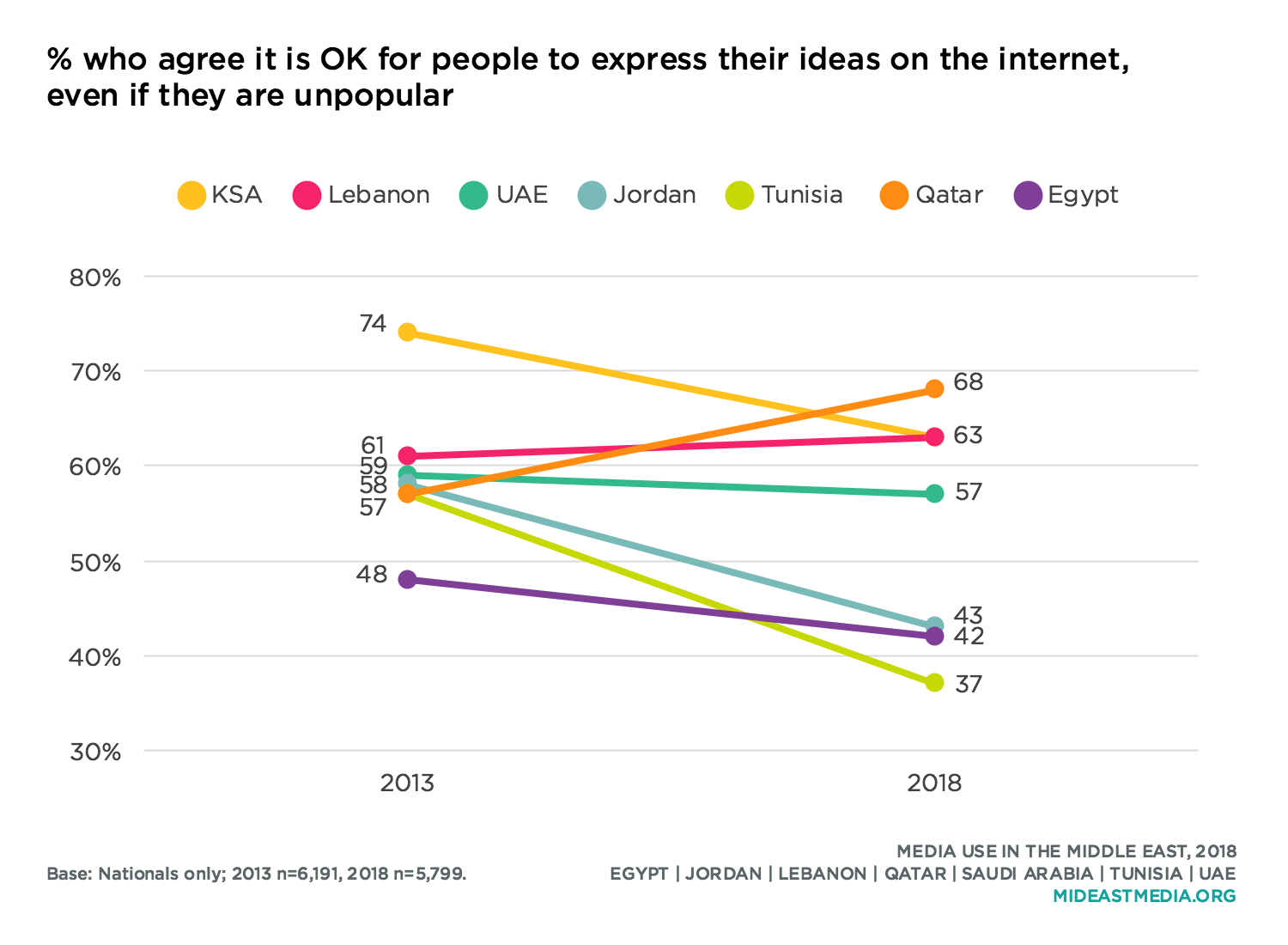

Compared to 2013, nationals in the seven countries surveyed in 2018 vary more their support for online freedom of speech. Fewer Tunisians, Egyptians, and Jordanians in 2018 than 2013 said that people should be able to express themselves online even if their ideas are unpopular, leaving less than half of nationals in each of these countries who agree. Majorities of nationals in all other countries say people should be able to express unpopular ideas online. The highest support for free speech online as of 2018 was in Qatar, where nearly seven in 10 nationals agree people should be able to express unpopular sentiments online.

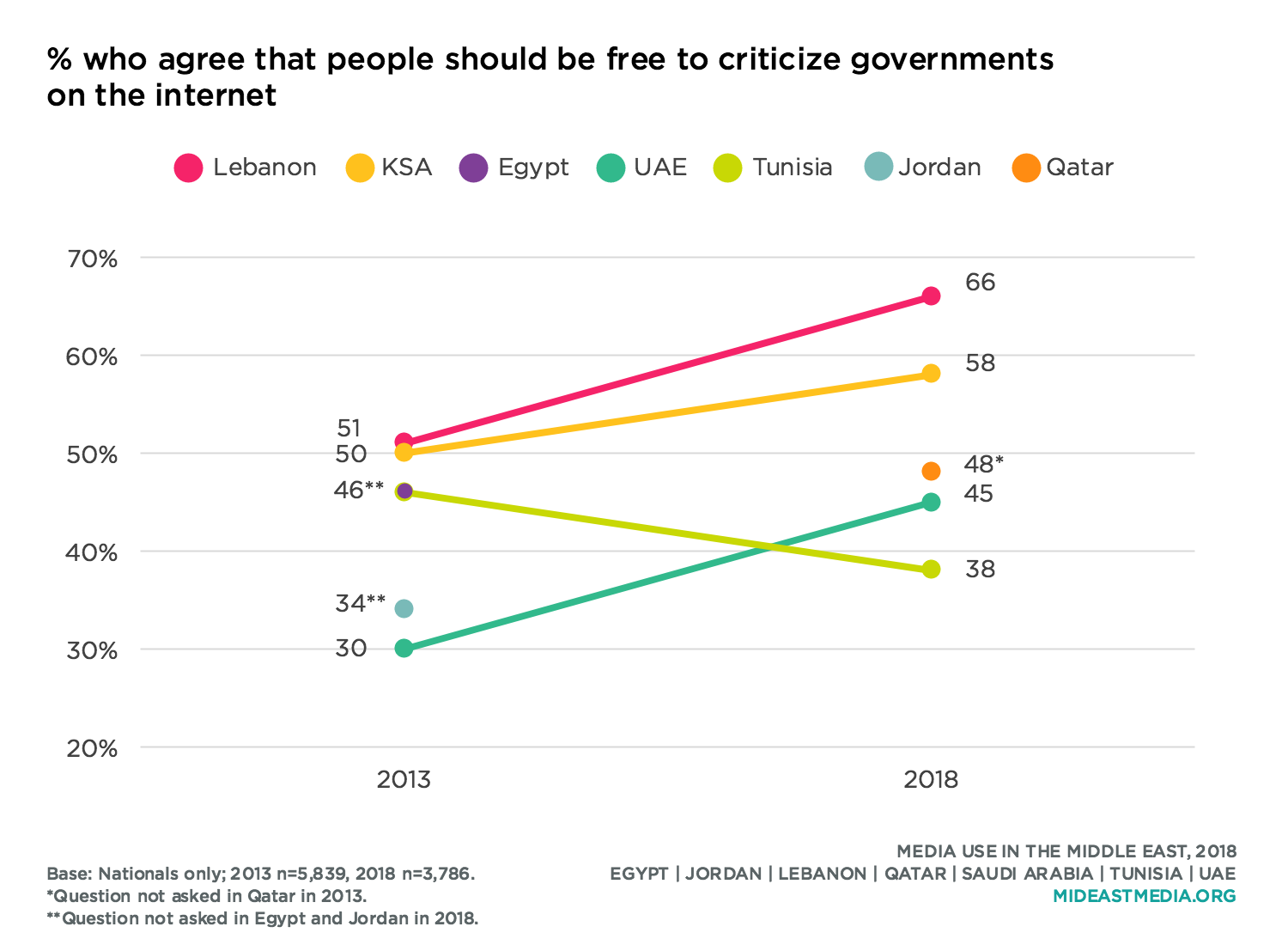

Between 38% and 66% of nationals in each country say people should be free to criticize governments on the internet (the low is in Tunisia, high in Lebanon), figures which have increased in Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE since 2013. Support for this form of free speech declined in the same period in Tunisia, however. This question was not permitted by officials in Egypt and Jordan.

In 2018, fewer nationals in the countries surveyed—half or less—said it’s safe to say on the internet whatever one thinks about politics, a decline since 2013 in all countries except the UAE (KSA: 58% in 2013 vs. 53% in 2018, Lebanon: 47% vs. 42%, Tunisia: 46% vs. 32%, UAE: 41% vs. 44%). This question was not permitted by officials in Egypt or Jordan in 2018 or in Qatar in 2013.

.png)

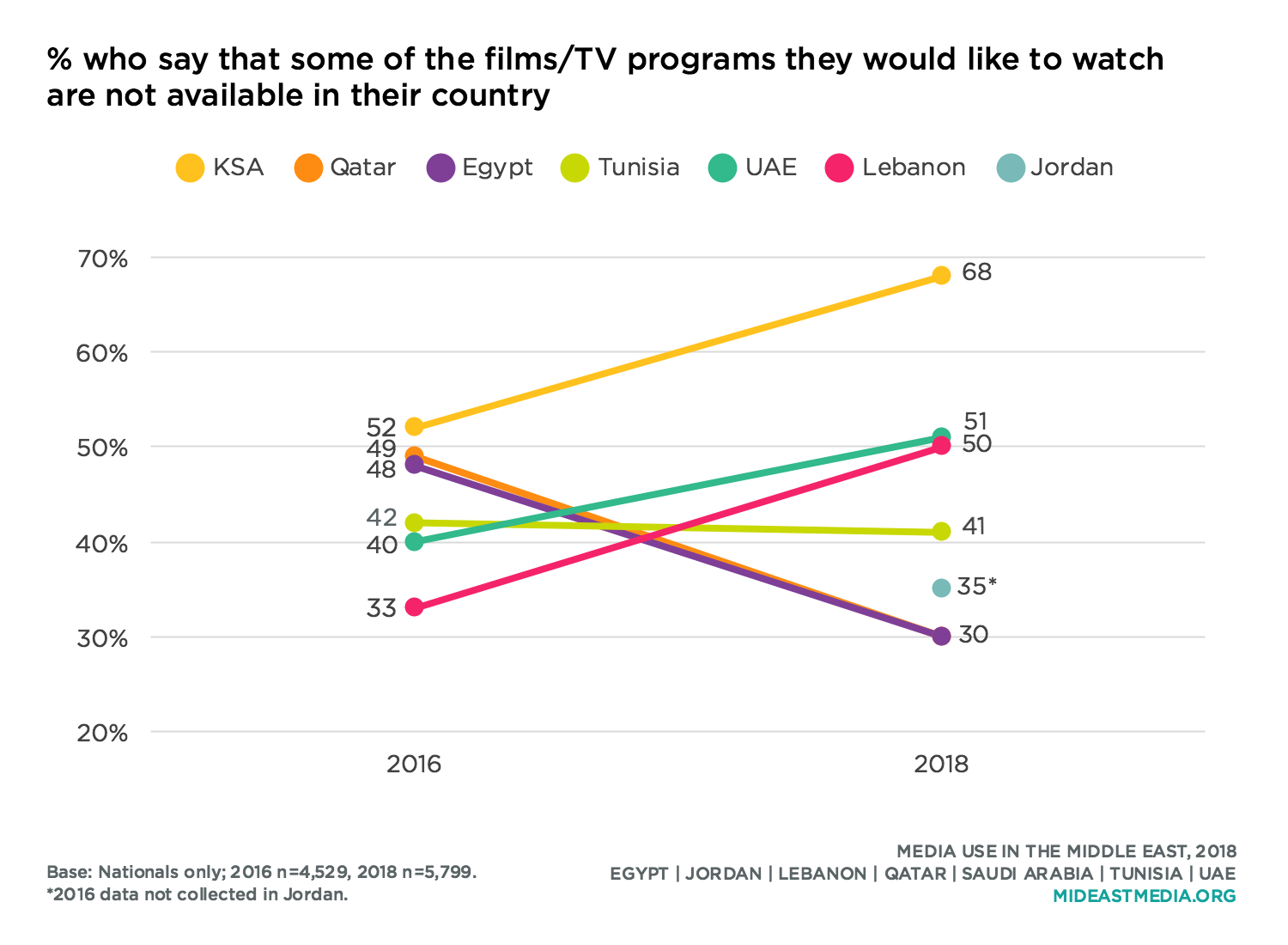

Majorities of Saudis, Emiratis, and Lebanese say some of the films and TV shows they want to watch are not available in their country—an increase of 10 percentage points or more in each country between 2016 and 2018. Qataris and Egyptians are the least likely to say content they want to watch is unavailable in their country, and figures have fallen in both countries since 2016.

Younger nationals, VPN users, and cultural progressives are more likely to say content they want to watch is unavailable in their country than are, respectively, older respondents, non-VPN users, and cultural conservatives (age: 50% 18-24 year-olds, 46% 25-34 year-olds, 40% 35-44 year-olds, 34% 45+ year-olds; VPN use: 56% yes vs. 45% no; 51% progressive vs. 41% conservative).

Increasing percentages of Arab nationals express concern about online privacy and surveillance, and this seems to affect their online behavior, or in the very least their perceptions of their online behavior. Nearly half of all nationals—up from two in 10 in 2017—say online privacy concerns have led them to change the way they use social media. Sharp increases were observed in all countries. This question was replicated by The Harris Poll and Northwestern University in Qatar in the U.S. in November 2018 for comparison purposes, and seven in 10 U.S. residents also say they changed social media behavior due to privacy concerns, which is similar to the figures among Saudis and Qataris.

More educated nationals than less-educated nationals say they have changed their social media behaviors due to privacy concerns, but still one-fifth with a primary education or less say they altered their social media use for privacy reasons (21% primary or less, 39% intermediate, 51% secondary, 58% university or higher). Self-described cultural conservatives are more likely than cultural progressives to have altered social media behaviors for privacy reasons (52% conservative, 42% progressive).

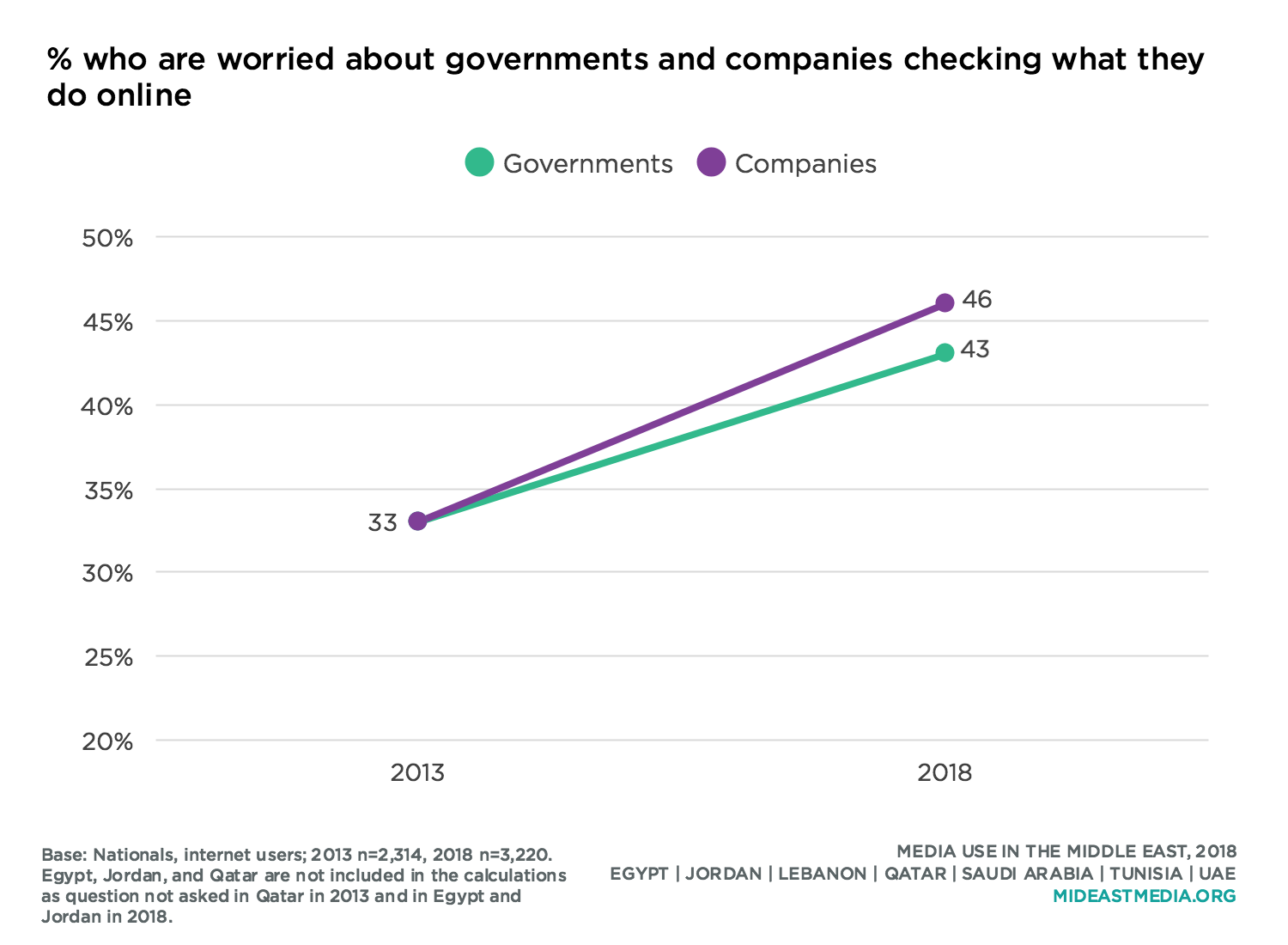

Internet users who say they are worried about governments and companies checking what they do online are far more likely to have changed their social media behavior than those who are not concerned about such surveillance (I am worried about governments checking what I do online: 74% who those agree vs. 43% of those who disagree say they have changed the way they use social media due to privacy concerns; I am worried about companies checking what I do online: 75% vs. 41%).

While no single social media platform is seen as a leader in terms of privacy safeguarding, a plurality of nationals—29 percent—say WhatsApp is the service that affords the most privacy. Notably, about one-quarter of nationals declined to cite any one network as the most private, perhaps reflecting a lack of confidence in social networks to protect privacy generally.

Concern about online surveillance by both governments and companies varies widely by country. More Saudi, Emirati, and Lebanese internet users than other nationals worry about both governments and companies monitoring their online behavior, figures that rose significantly since 2013. About one in three Tunisian internet users expressed the same concerns, figures unchanged since 2013.

Fewer Qataris than other nationals are worried about either governments or companies surveilling them online. U.S. residents are more concerned than Arab nationals about companies checking their online activities, and are on par with Saudis with regard to concern about government surveillance.

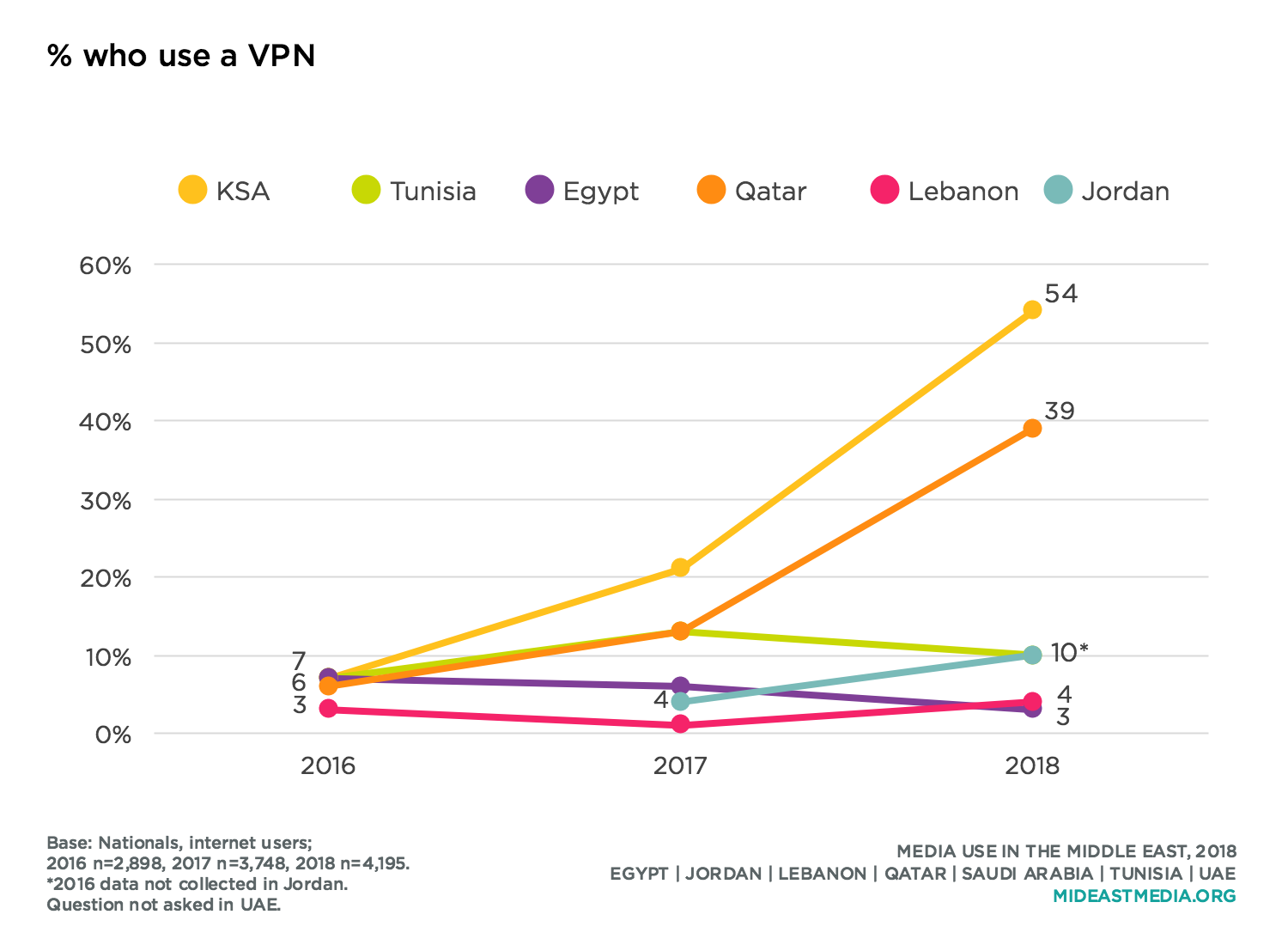

There were large increases between 2017 and 2018 in the percentages of Saudis and Qataris who use a VPN—now at 54% and 39%, respectively—but figures are much lower among nationals in the other countries in the study: 10% of nationals or less.

Younger and more educated nationals are more likely to use a VPN (age: 21% 18-24 year-olds, 17% 25-34 year-olds, 16% 35-44 year-olds, 14% 45+ year-olds; education: 17% university or higher, 20% secondary, 8% intermediate, 7% primary or less).

Nationals who say privacy concerns have changed the way they use social media are more than three times as likely to use a VPN as those who say they haven’t changed their online behavior (25% vs. 7% use a VPN). Additionally, internet users who are worried about government surveillance online are more likely than those who are unconcerned about surveillance to use a VPN (29% vs. 19%, respectively).

Digital Privacy in a Post-Blockade Middle East

Kristian Ulrichsen, Rice University

The political polarization in large parts of the Middle East is reflected in several of the 2018 findings on how people in the region perceive issues that pertain to censorship and digital privacy. The results indicate not only a significant divergence in public attitudes toward freedom of expression across countries but also a sharp increase in concerns about digital privacy and online surveillance. While such patterns are observable over a five-year period since 2013, there has been an especially noticeable jump in several indicators since 2017, illustrating the depth of concern many in the Middle East have on these issues.

With many governments in the Middle East appearing more authoritarian today than they did in 2011, the ‘post-Arab Spring’ landscape finds expression in greater concern about government surveillance as well as wariness of presenting views openly on social media and the internet more generally.

Many more people in 2018 are worried about governments and companies checking their online activity than in 2013, with Lebanon showing that such concerns are not limited to Gulf States (Saudi Arabia and the UAE). This likely reflects greater awareness of privacy and surveillance in the wake of high-profile cases where people have been detained and prosecuted under expansive new cybercrime and terrorism legislation that has been passed in recent years.

There are some interesting differences in how respondents perceive various aspects of freedom of expression, with a clear downward trend over five years in support of people expressing their ideas on the internet versus a broadly upward-trend in those who feel people should be free to criticize governments online. This is most pronounced in Saudi Arabia and illustrates the complexity of social issues facing Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman as he consolidates political authority in the Kingdom.

Inevitably, rising awareness of the darker side of internet use has translated into differences in the ways people in the Middle East engage with each other online and interact on social media. In every state bar Egypt, concerns for privacy have dramatically changed the way people use social media, which has resembled a toxic battleground of accusation and abuse both by human users and electronic bots.

The proportion of respondents using a VPN more than doubled in Saudi Arabia and Qatar between 2017 and 2018 while WhatsApp was by far the most-trusted social media platform in terms of privacy for users. The online ‘free-for-all’ that characterized social media use during and immediately after the Arab Spring has given way to deep mistrust of most platforms and acknowledgment that online interaction carries costs as well as benefits.

Several factors may account for the far higher use of VPNs in Gulf States compared with elsewhere in the Middle East. There is a greater level of surveillance in the Gulf that intersects with an increased sensitivity over what is ‘safe’ to say and do in settings most assume are open to penetration by security forces. The hacking incidents that preceded and accompanied the outbreak of the Gulf crisis between Qatar and three regional neighbors in June 2017 provided visible reminders of the need for added security in internet use.

The 2018 findings provide the first real snapshot of opinion since the Gulf crisis began. Already, several clearly diverging trajectories emerge. There has been a broad rise in support in Qatar for free speech online which contrasts with the downward trajectories in Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Egypt, three of the four states that cut ties with Qatar in 2017. This is consistent with observable notions that Qatar has responded to the crisis by becoming more open as a society while political repression in Egypt, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia has intensified.

A finding that cuts across sub-regions in the Middle East is broad support for tighter regulation of entertainment, probably because every country has socially conservative constituencies, but this consensus breaks down when it is asked about tighter regulation of the internet. Significant increases in support for tighter internet regulation in Egypt and the UAE track the authoritarian turn in both countries, but there is no change in support in Saudi Arabia, despite the political crackdowns since 2017.

Throughout the Middle East, people are more concerned than ever about the possibility of intrusive state monitoring of online and social media activity. That some of the notable increases in concern are in Lebanon should caution observers from imagining that this is a phenomenon mostly rooted in the Gulf, although rising Gulf influence in Lebanon since 2013 may be feeding into these results.