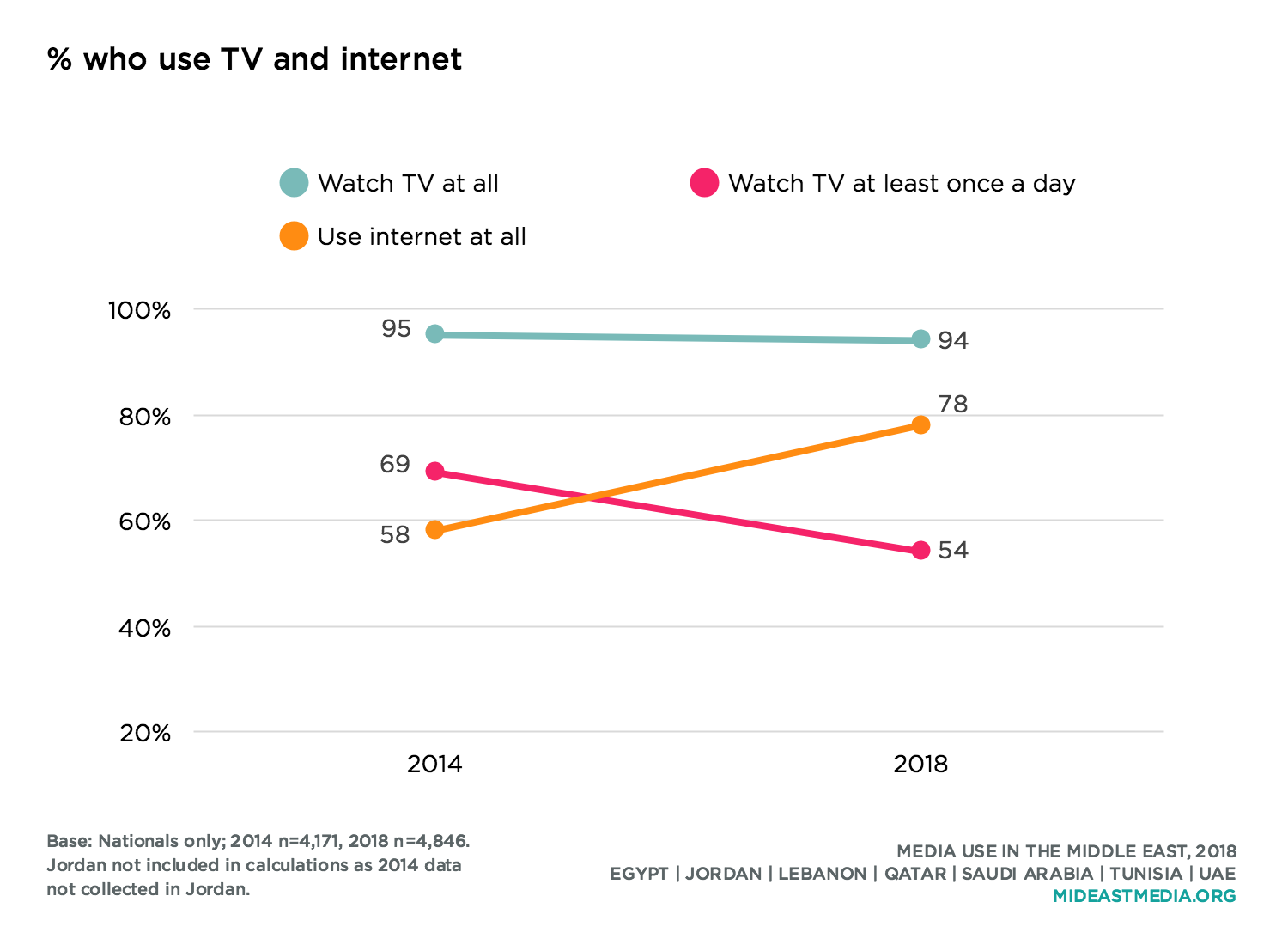

TV remains an important entertainment medium in the Middle East, but how Arab nationals watch TV, and how often, is changing. Almost all nationals watch TV, but significantly fewer watch TV every day compared to 2014 (69% in 2014 vs. 54% in 2018). At the same time, nationals are now more likely to go online for entertainment on a daily basis—to watch videos, listen to music, get news, and watch films online (do at least once a day, watch videos online: 30% in 2016 vs. 40% in 2018; listen to music online: 22% vs. 28%; check news online: 29% vs. 34%; watch films online: 9% vs. 15%).

Nearly nine in 10 nationals across all age groups watch at least some TV, but younger respondents are less likely to watch TV every day (44% 18-24 year-olds, 48% 25-34 year-olds, 54% 35-44 year-olds, 61% 45+ year-olds).

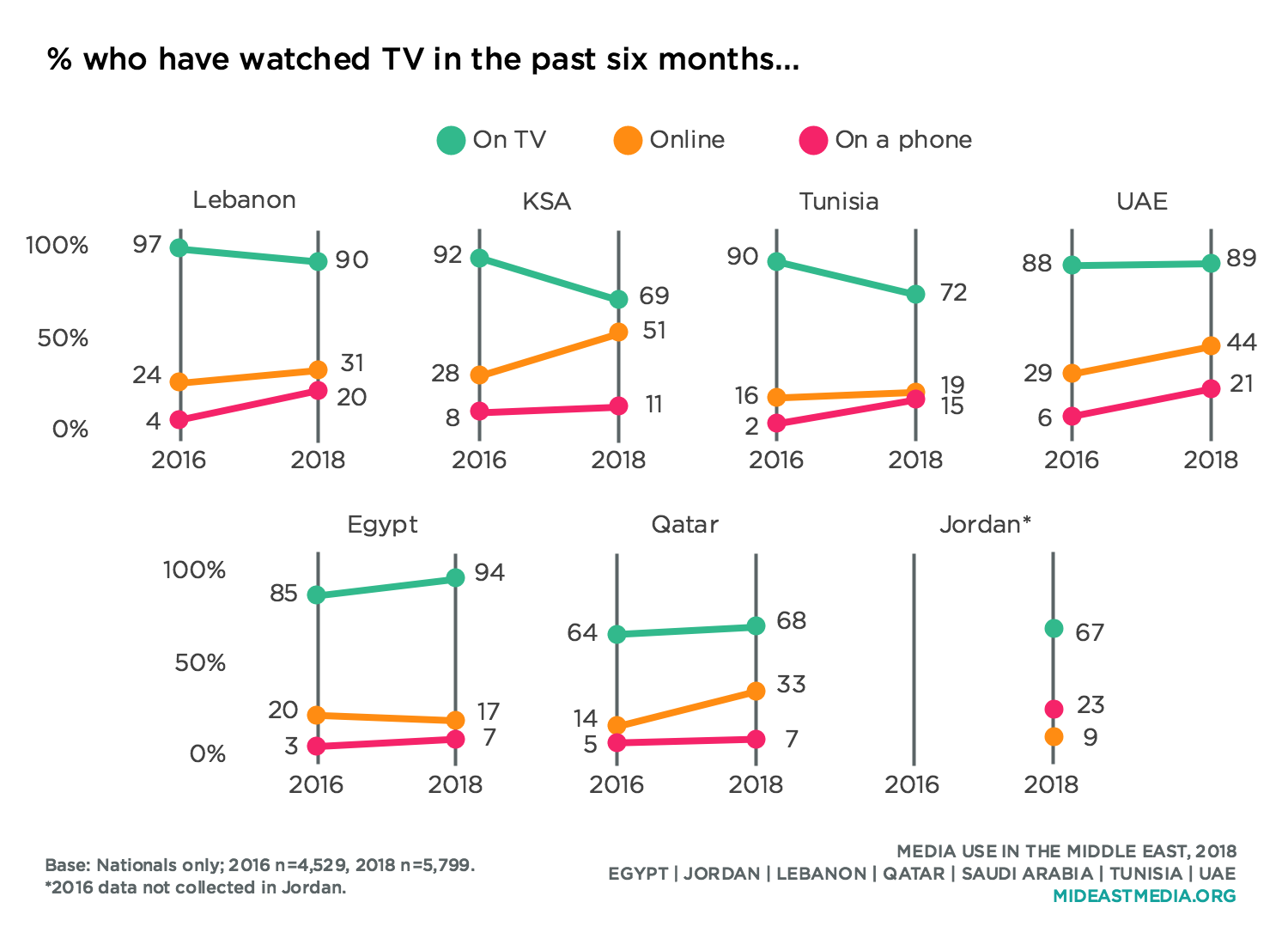

Actual TVs are the primary means nationals use to watch TV shows, but since 2016 the proportions watching both online and on a phone have increased. Online viewing of TV shows increased most dramatically in the Arab Gulf countries studied—by 15 percentage points or more in Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE.

The youngest nationals watch TV online and on phones at rates double or more than the oldest age group (online: 33% 18-24 year-olds, 32% 25-34 year-olds, 23% 35-44 year-olds, 11% 45+ year-olds; on a phone: 20%, 17%, 12%, 10%).

Eight in 10 nationals watch TV on an actual television, a figure that does not change across levels of education. However, fewer than 10% of the least educated (primary school or less) watch TV online or on a phone, compared to more than double that rate among those with a university education (online: 6% primary or less, 17% intermediate, 28% secondary, 34% university or higher; on a phone: 6%, 13%, 17%, 17%).

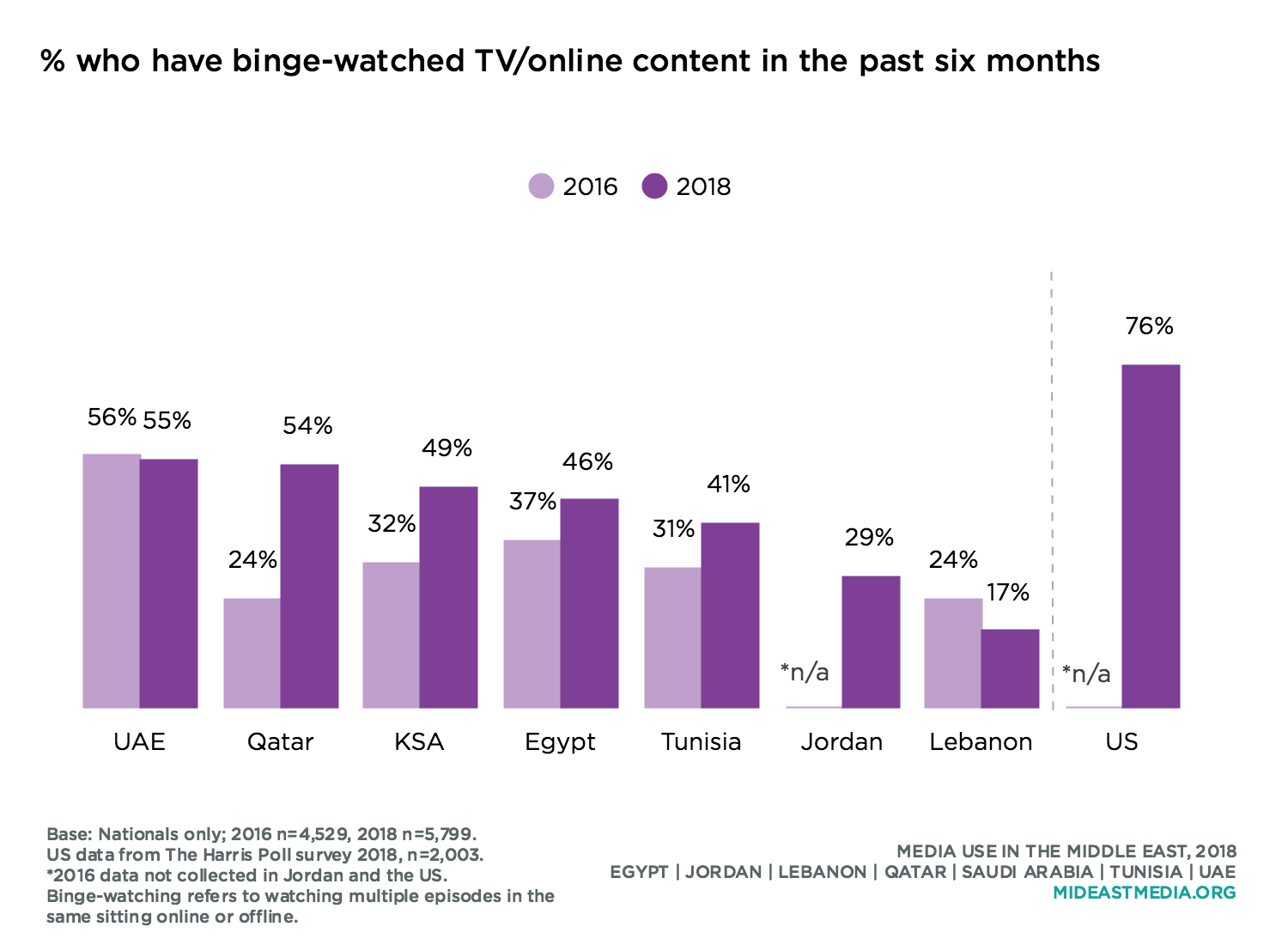

More nationals report binge-watching TV series, that is, watching multiple episodes of entertainment content online or on TV in the same sitting. Half or more of Qataris, Saudis, and Emiratis say they have binge-watched content in the past six months, which represents sharp increases in Qatar and Saudi Arabia since 2016. And more than four in 10 Egyptians and Tunisians binge-watch TV. Binge-watching is less common in Jordan and Lebanon. Binge-watching in all the Arab countries in this study is less common than in the United States, where three-quarters of internet users say they have binge-watched content in the past six months.

Women are more likely than men to have binge-watched a TV series in the past six months (46% vs. 30%, respectively). Binge-watching is also more prevalent among younger nationals (46% 18-24 year-olds, 41% 25-34 year-olds, 36% 35-44 year-olds, 27% 45+ year-olds).

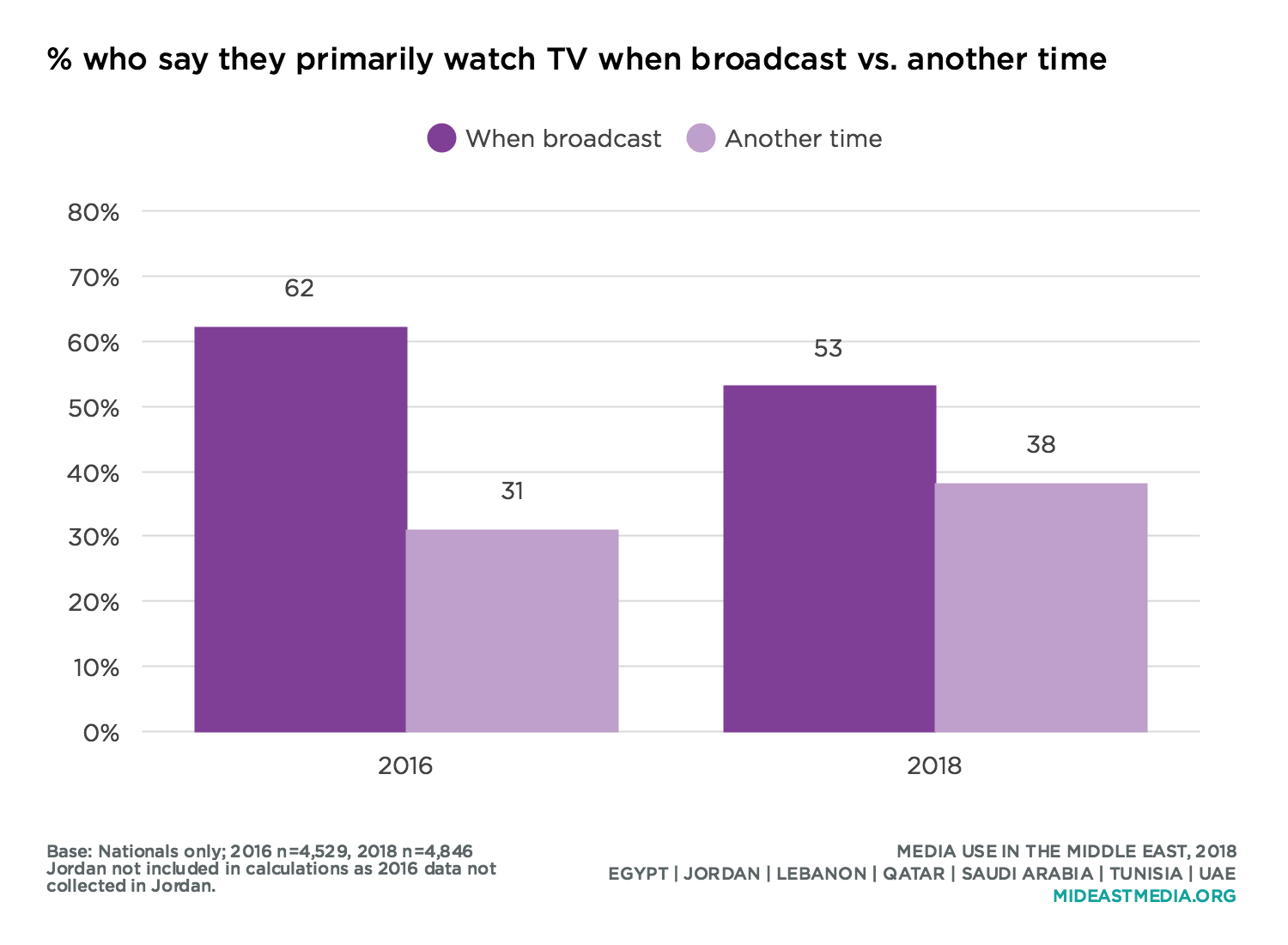

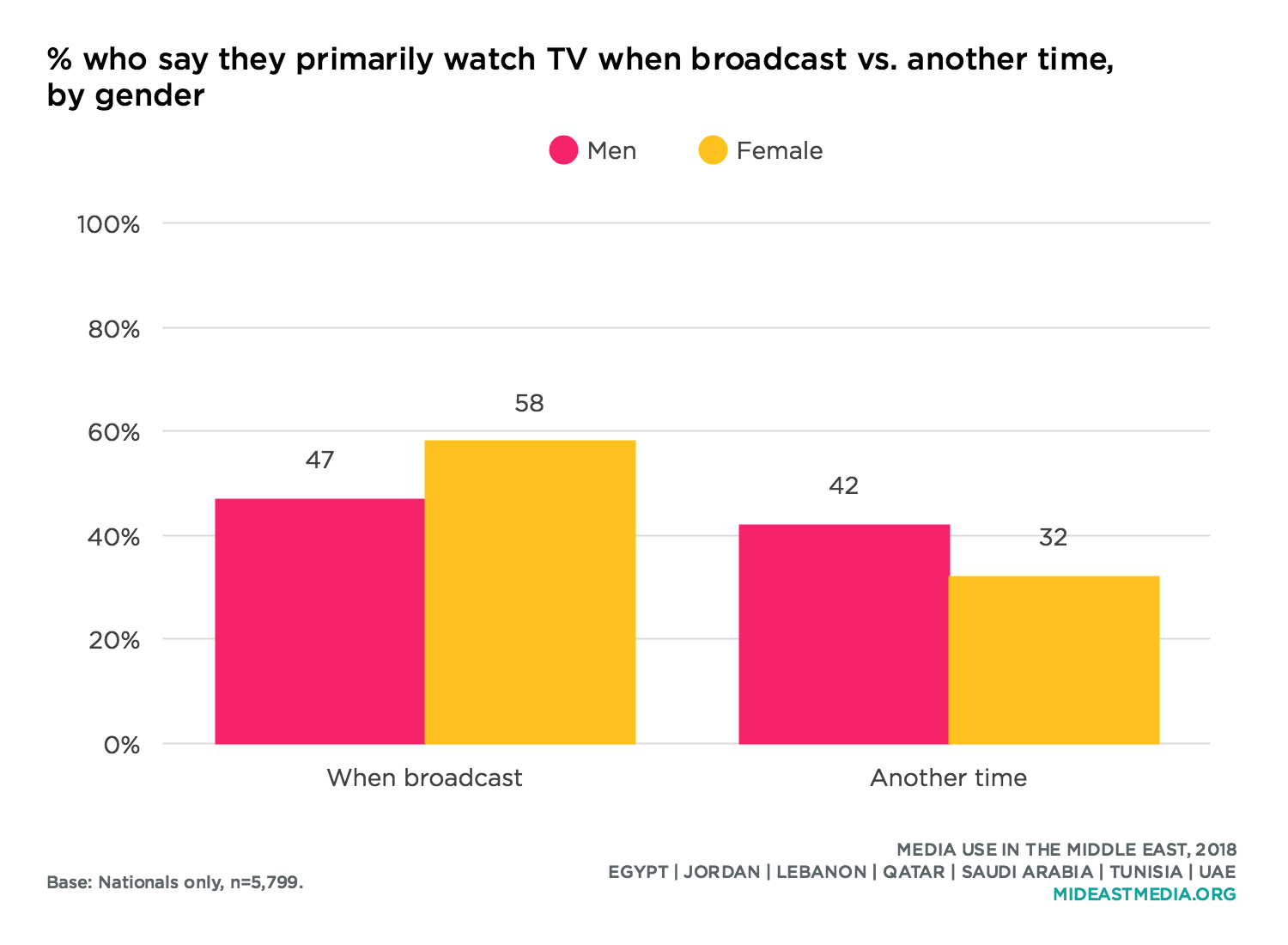

As in 2016, Arab nationals tend to watch TV when the show is broadcast rather than at another time. Still, the gap between the share of respondents that says they mostly watch TV at broadcast time and the share that watches at their convenience has narrowed.

Women tend to watch TV shows when they are broadcast, while men are more likely to watch TV content at another time.

Older nationals tend to watch TV shows at the time of broadcast, but half of the youngest nationals also watch TV at the scheduled time (when broadcast: 48% 18-24 year-olds, 50% 25-34 year-olds, 55% 35-44 year-olds, 58% 45+ year-olds; another time: 42%, 40%, 36%, 29%).

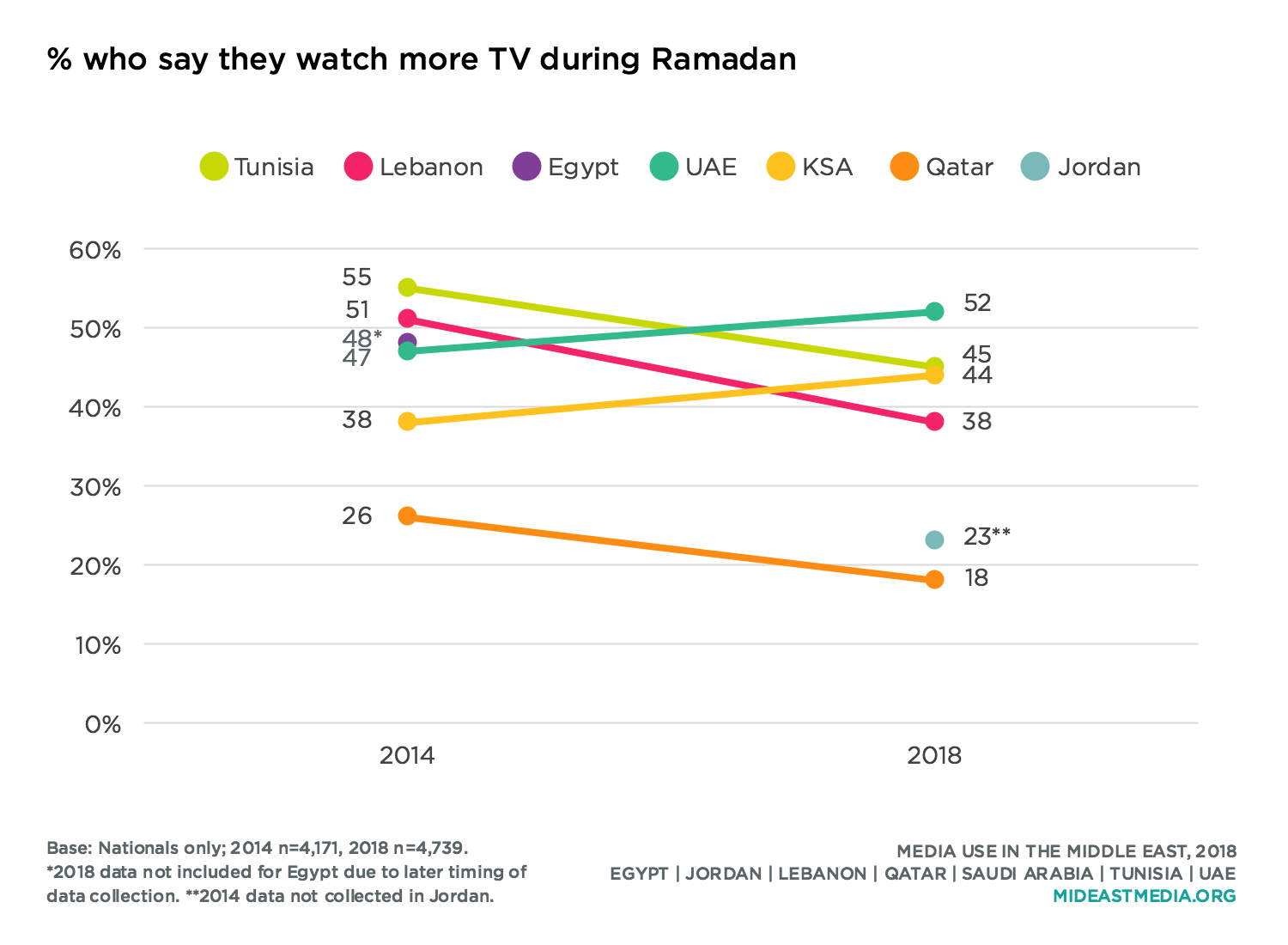

Watching TV is the media activity Arab nationals are most likely to do more of during Ramadan. Nearly half of Arab nationals also say they spend more time consuming entertainment media with their families during Ramadan.

About half of Saudis, Tunisians, and Emiratis say they watch more TV during Ramadan, an increase in both Saudi Arabia and the UAE since 2014 but a decline among Tunisians. The proportion who watch more TV during Ramadan also dropped in Lebanon and Qatar.

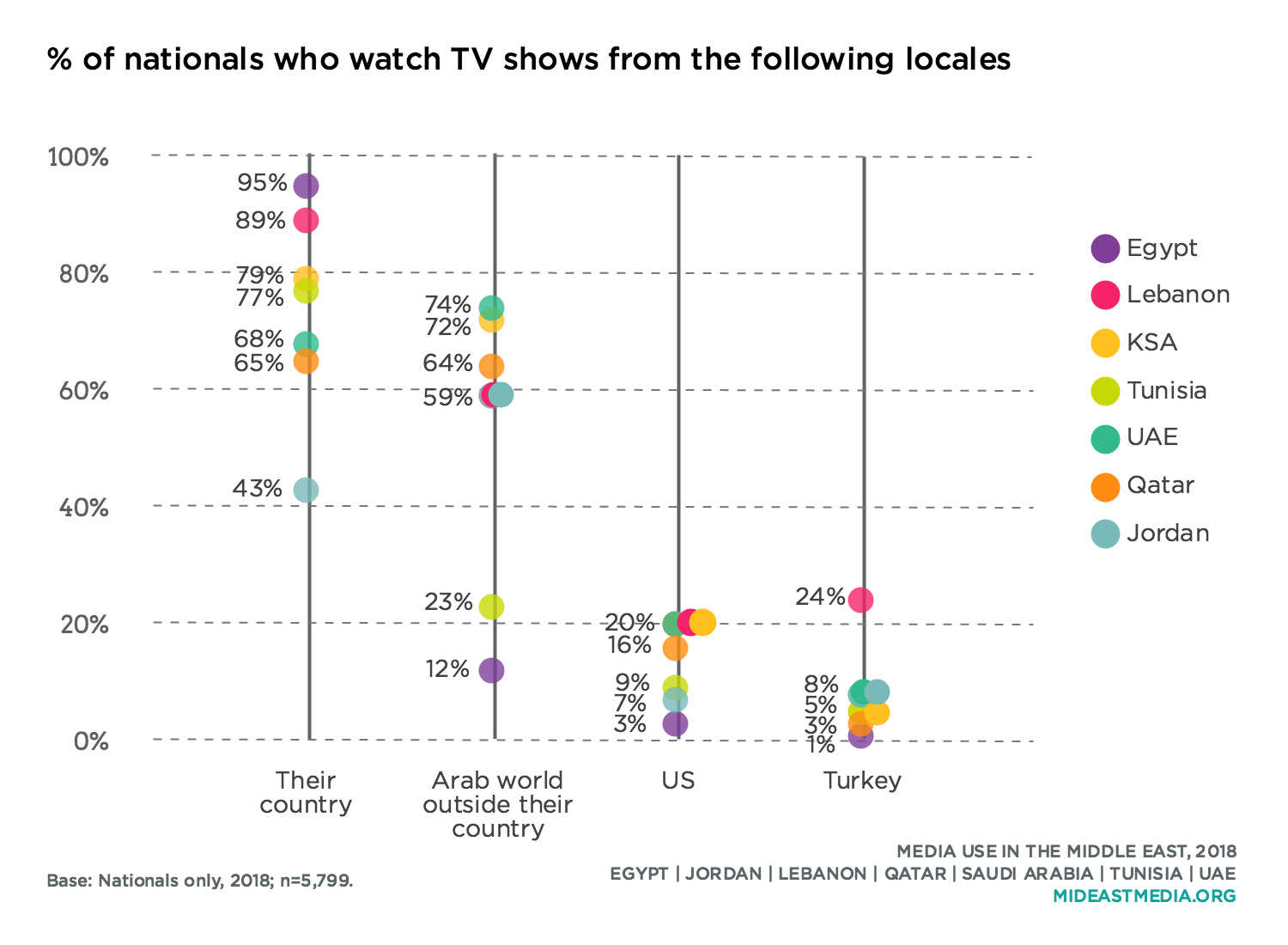

Significant majorities of nationals in each country prefer shows from their own country or from other Arab nations (except in Jordan, where only four in 10 watch such programming). Almost all Egyptians watch TV programs from their own country, but only one in 10 watch shows from other Arab countries. Emiratis and Saudis watch TV programs from other Arab nations at the highest rates. About one in five nationals in Lebanon, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE watch TV programs from the U.S. One-quarter of Lebanese nationals watch Turkish TV content.

Education appears to be a more significant factor with regard to watching TV content from Western countries than from the Arab region. At least three-quarters or more of Arab nationals across all educational categories watch shows from their own country, and half of those with a secondary education or more watch programming from other Arab nations. Nationals with at least a university education, however, are significantly more likely to watch Western TV content than those with a primary education (U.S. shows: 19% university or higher, 13% secondary, 4% intermediate, 1% primary or less; European shows: 13% university or higher, 9% secondary, 4% intermediate, 2% primary or less).

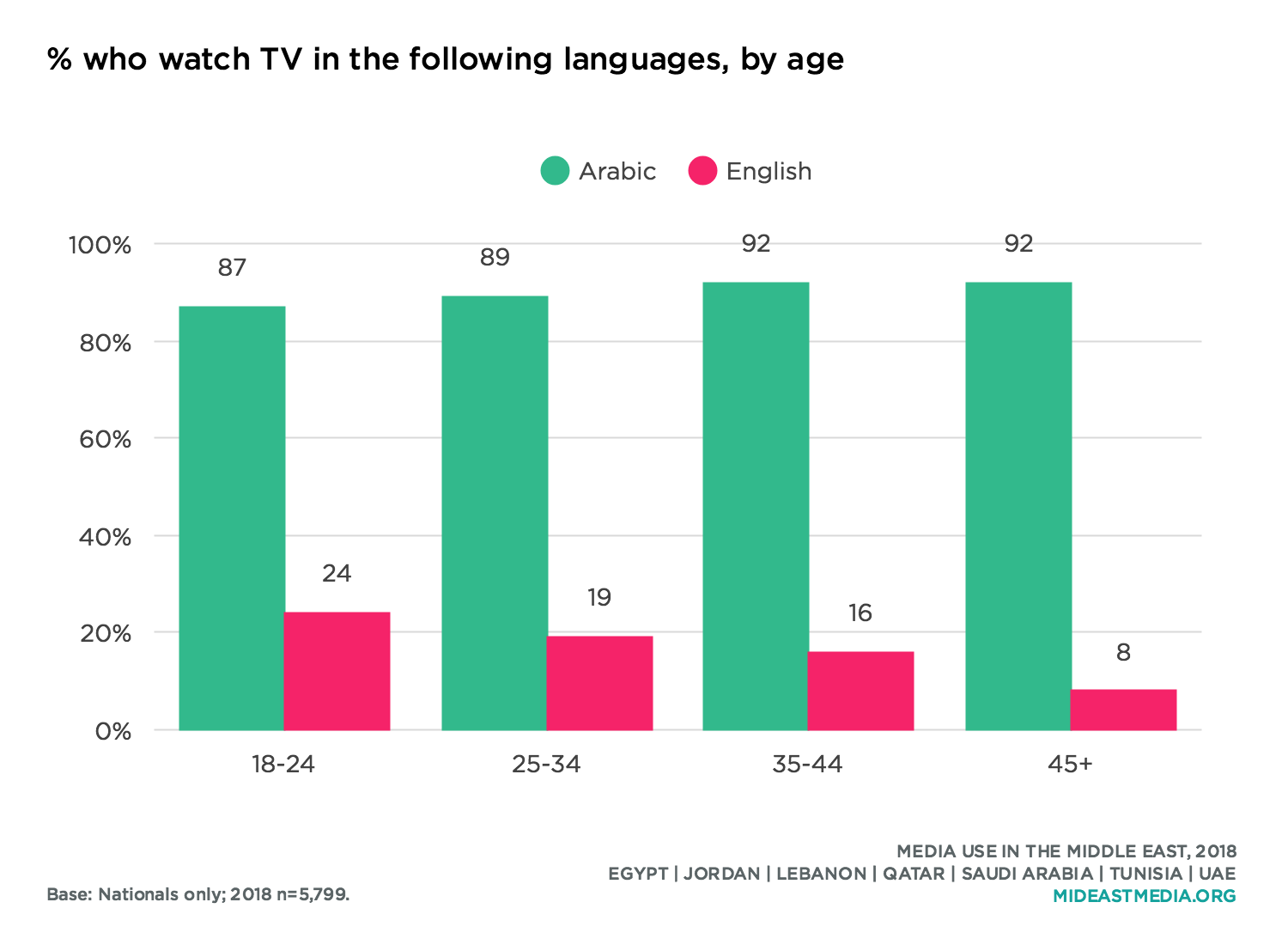

Nine in 10 Arab nationals watch TV content in Arabic, compared to nearly two in 10 who watch in English, though figures differ considerably across countries for English content, from a high of 35% in the UAE to a low of 3% in Egypt. Tunisia and Lebanon are the only countries in which a modest number of nationals watch TV in French (16% and 7%, respectively).

Nine in 10 nationals across all age groups watch TV in Arabic. However, nationals under the age of 45 are two to three times more likely to watch TV programs in English than those 45 and older.

Education is positively associated with watching TV in English. Nationals with at least a college degree are eight times more likely than the least educated nationals to watch TV in English (3% primary or less, 7% intermediate, 19% secondary, 25% university or higher). Nationals who self-identify as culturally progressive are also more likely to watch TV in English than those who identify as culturally conservative (31% progressive vs. 14% conservative).

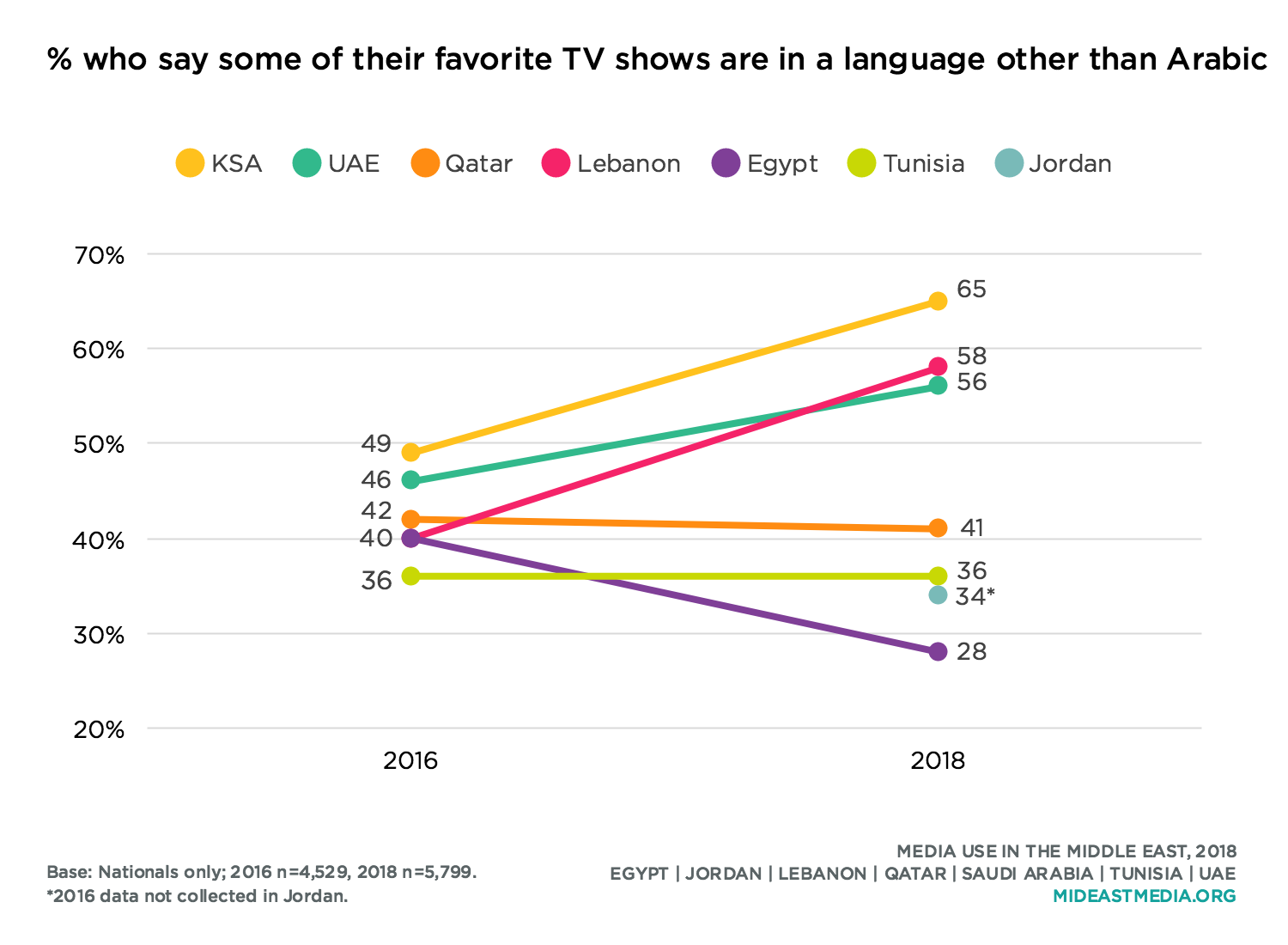

Nationals are far more likely to watch English-language filmsthan English-language TV. Compared to 2016, though, more Arab nationals in 2018 agree with the statement: some of my favorite TV shows are in a language other than Arabic (41% in 2016 vs. 45% in 2018). Majorities in Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE say some of their favorite TV programming is not in Arabic, and at least one-third of nationals in the other countries agree. The proportion of nationals in Qatar and Tunisia whose favorite TV programs include non-Arabic content did not change between 2016 and 2018, but the figure rose among Lebanese, Saudis, and Emiratis. Egyptians are the only nationals less likely in 2018 than 2016 to say some of their favorite shows are in a language other than Arabic.

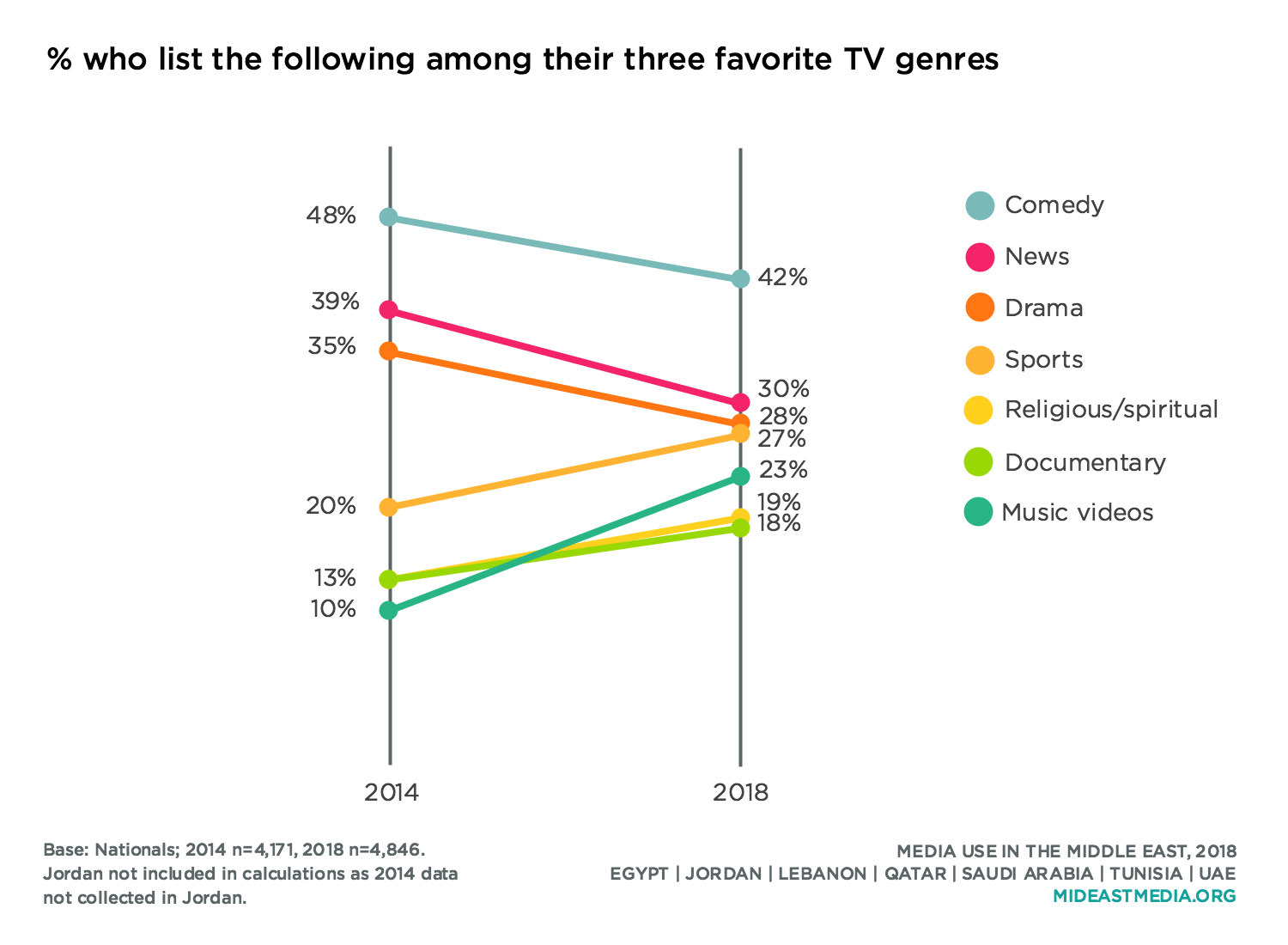

Nationals’ three favorite TV genres have remained the same since 2014—comedy, drama, and news—but fewer list these genres as favorites than did so in 2014, as more nationals turn to the internet for news and as other genres have increased in popularity. The share of nationals listing music videos as a favorite TV genre increased by 13 percentage points between 2014 and 2018, those citing sports by seven points, those choosing religious/spiritual genres by 6 points, and documentaries by 5 points.

Several changes in TV genre preferences are notable at the country level. The percentage of Lebanese who list news as a favorite genre fell by nearly half, from 51% in 2014 to 27% in 2018, while preferences for music videos, documentaries, and reality shows nearly doubled in the same period. Religious/spiritual content was listed as a favorite genre by 35% of Qataris in 2014, a figure that dropped to 23% by 2018. At the same time, popularity of comedy, drama, and news all increased in Qatar.

In Saudi Arabia, interest in religious/spiritual content as a favorite genre increased exponentially from 5% in 2014 to 33% in 2018. Preferences for sports and music videos also doubled and tripled, respectively, in Saudi Arabia since 2014. In Tunisia, the share of Tunisians citing music videos among their TV favorite genres nearly tripled between 2014 and 2018. In the UAE, sports as a favorite genre jumped from among 17% of nationals in 2014 to 42% in 2018. Interest in music videos also increased significantly among Emiratis.

Genre preferences vary by gender. Women are more likely than men to list dramas, religious/spiritual programming, fashion content, and talent shows among their favorites (drama: 34% women vs. 23% men; religious/spiritual: 24% vs. 16%; fashion: 19% vs. 3%; talent shows: 19% vs. 15%). Men, on the other hand, are more likely than women to prefer news, sports, and documentaries (news: 40% men vs. 24% women; sports: 44% vs. 7%; documentaries: 23% vs. 15%).

While many Arab nationals watch TV shows online, very few paid for online TV content in the past year, ranging from the highest rates (still less than 10% of nationals) in the UAE to barely anyone in Lebanon or Qatar (8% UAE, 5% KSA, 4% Tunisia, 2% Jordan, 2% Egypt, 1% Lebanon, 1% Qatar).

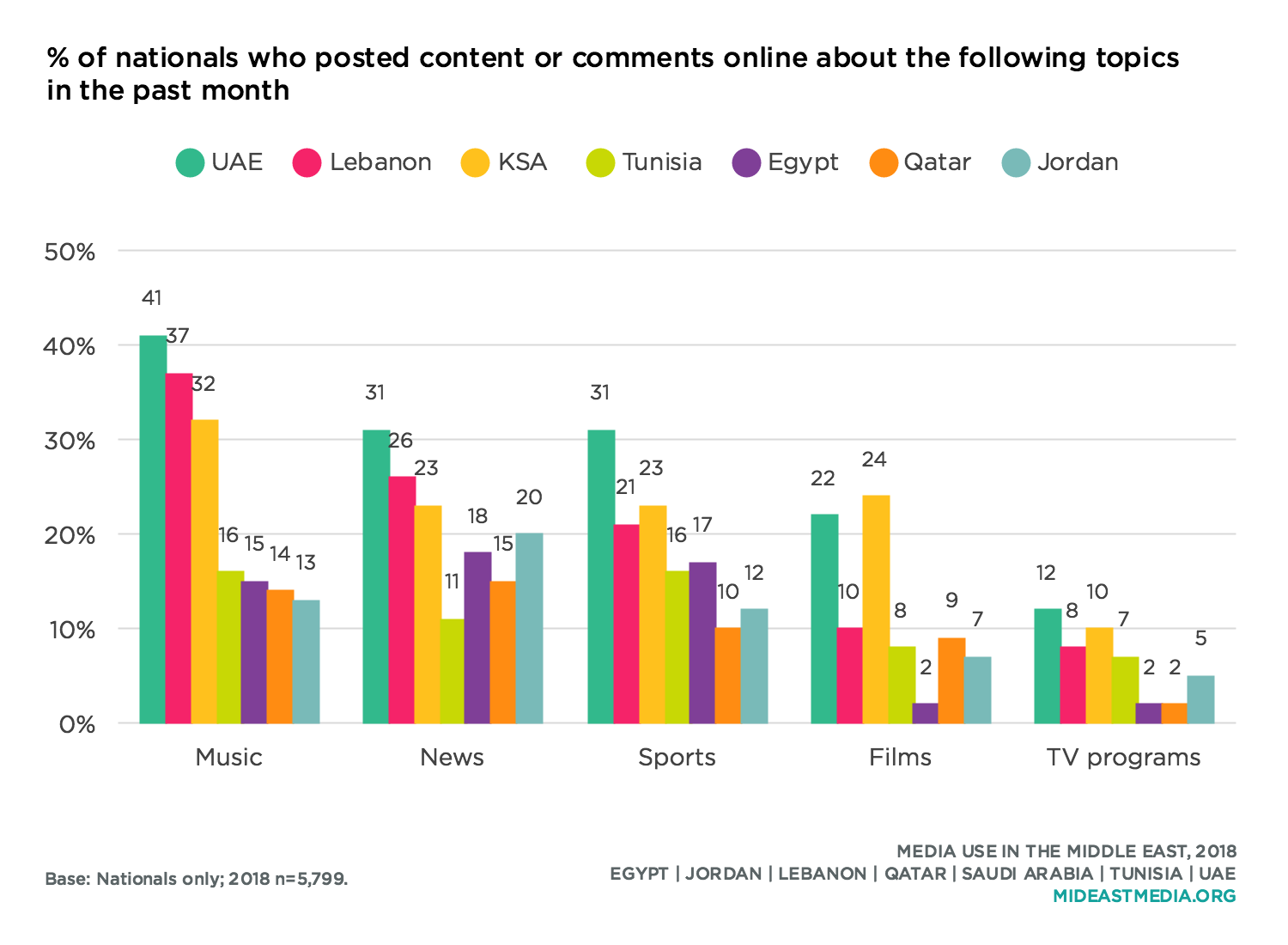

Arab nationals are also not inclined to post about TV programs online. Only one in 10 or fewer across countries say they sent, shared, or posted content or comments online about TV shows in the past month, much less than the share of nationals who posted about each music, news, sports, or films in the same time period. Fewer than 10% of any demographic group across gender, age, or education level have posted online about TV shows in the past month.

The Changing Television Landscape

Marwan M. Kraidy, Annenberg School for Communication - University of Pennsylvania

Television remains the queen of media in the Arab world, but this regal status is changing every year. Arab nationals no longer watch television every day, and when they do it is increasingly online or on their mobile device. These trends have been around for at least a half-decade, but many are now crossing thresholds that will affect the way that society and individuals relate to television.

How the new television practices will change social rituals is an issue to watch. Traditionally, television viewing in the Arab World is a family practice. This is particularly the case during the Holy Month of Ramadan when media companies air the very best in television drama, comedy and game shows. Programming takes off as viewers break their fast with a lentil soup, continues as they sample a feast, and ends past dessert time.

How this pairing of religious ritual, festive eating, and television viewing will be challenged by online and particularly mobile viewing, goes to the heart of Arab concerns about media and changing social norms. Not having to wait for your favorite show to be broadcast has its appeal, and so does the ability to watch it on your mobile device on your own while lying on your bed.

However, trends like binge-watching, which are at face value, not healthy practices, risk reigniting Arab culture wars that have been dormant for years. For example, ten years ago, one of the standard lines of attack against Arab reality television in the Gulf and elsewhere, was that “it killed time,” by compelling people to watch contestants’ daily lives for hours at a time. This was done first through dedicated satellite channels, then online live streams. Nowadays, every middle-class Arab teenager carries a “permanent TV” interface in their pocket.

Television viewing used to punctuate the daily routine. It was a rather predictable part of one’s daily rhythm, and it typically occurred in the evening. Now there is a risk that television viewing is undergoing a disconnection from daily life: it is either completely delinked from people’s daily routine, or it totally dominates one’s day. The tempo of television watching is changing as much as the technology of access with consequences for family life, social tradition, and national cohesion.

One interesting finding in that regard is gender differences among Arab nationals watching television when broadcast versus another time. More men than women watch television at “another time,” presumably via on-demand digital platforms, whereas less than half of men compared to two-thirds of women watch television “when broadcast.” This suggests that women, perhaps because they remain the primary homemakers and caregivers, have less fewer opportunities than men to watch television at non-scheduled hours. Gender differences are poised to increase as digital media choices multiply.

Arab nationals’ decisive preference for television in their native language is in sync with patterns identified by researchers worldwide since the 1980s: when attractive domestic productions are available, viewers prefer watching material that resonates linguistically, socially and culturally. The quantity and quality of Arab television production have grown in leaps and bounds in the last quarter century, particularly in drama, comedy, and news, precisely the three TV genres that remain Arab nationals’ favorite shows.

In contrast, it is not surprising that whereas 9 out of 10 Arab nationals prefer to watch Arabic-language television, they are far more likely to watch English-language films. Whether this means they prefer films dubbed in English or films originally produced in English is unclear, what is irrefutable is that the Arab film industry remains woefully underdeveloped. Some documentaries and auteur films have met critical and limited commercial success, but nowadays even Egypt—once the Hollywood of the Arab world—struggles to produce mass entertainment blockbusters.

At the same time, the rise of the popularity of platforms like Netflix is likely to accelerate a trend whereby more Arabs watch non-Arabic language television, particularly English-language productions. The fact that very few Arab nationals have paid, or are willing to pay, for online television content, is likely to be one of the most formidable challenges for the expansion of Netflix and its global and local competitors. Similarly, as we have recently seen in Canada, the spread of online streaming platforms like Netflix whose business model often does not contribute financially to the communities where its viewers reside may lead to renewed cries of cultural imperialism.

It is also interesting that screens and images now reign supreme among Arab nationals. After several years of significant declines in newspaper readership across the region, Arab societies are moving decisively into public spheres dominated by digital images. Whereas this has been the case in the West for at least a half-century, Arab nations lack the legal frameworks necessary to regulate the proliferation of images at an unprecedented scale and will need to upgrade these frameworks to keep up with changing television distribution and reception patterns.