Of the six nationalities in this study, Qataris demonstrate the most unique social media use patterns. Most internet users in Qatar use WhatsApp (93%) and about two-thirds use Instagram and Snapchat (70% Instagram, 64% Snapchat). This latter percentage represents perhaps the highest Snapchat penetration of any country in the world.

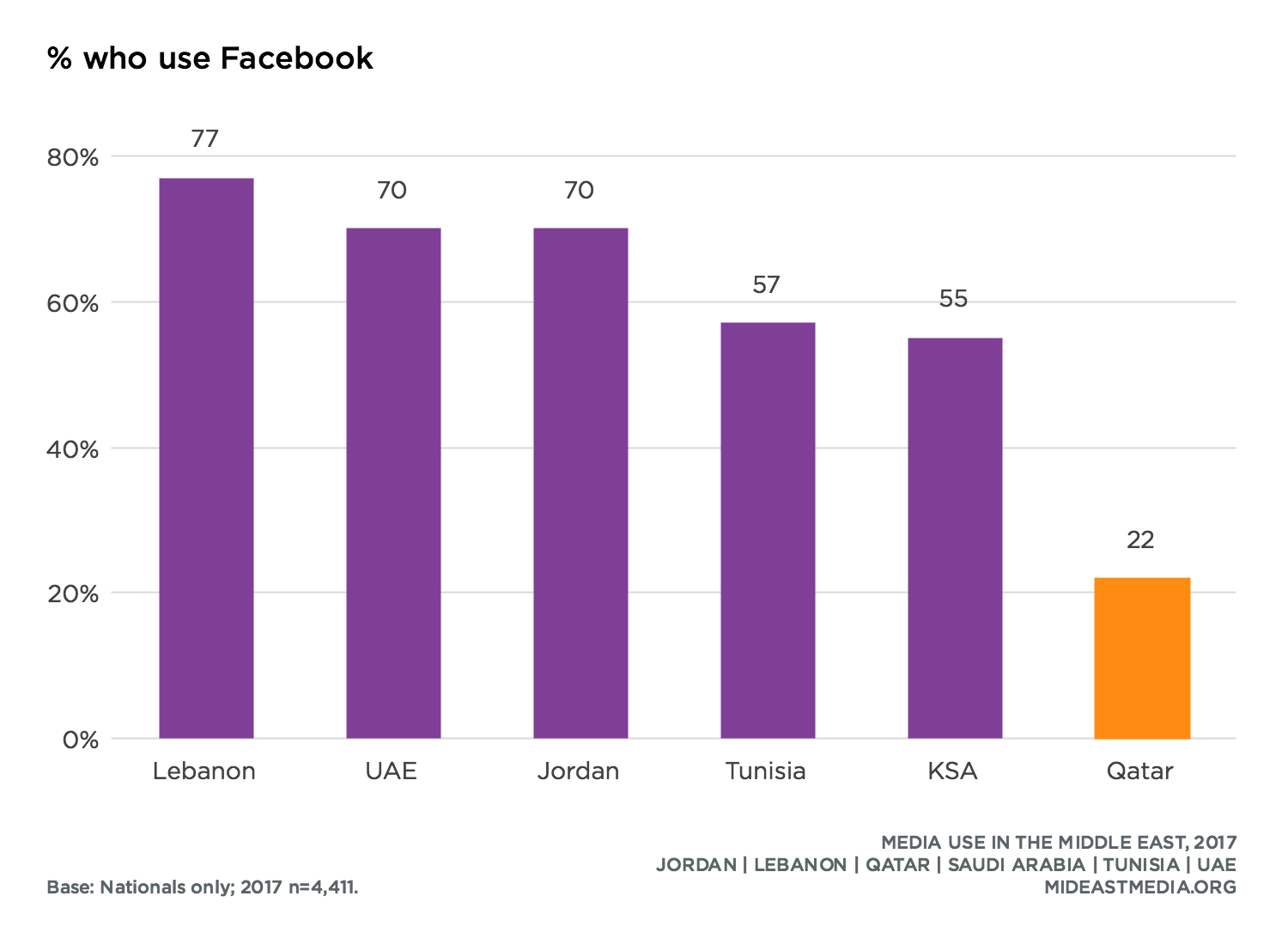

However, fewer than one in four Qatari internet users use Facebook (23%), one of the lowest Facebook penetration rates among wealthy countries. Nearly half of Qatari internet users use Twitter and four in 10 use YouTube (48% Twitter, 39% YouTube). In other countries surveyed, Facebook penetration is more robust among internet users(71% UAE, 87% Jordan, 84% Lebanon, 83% Tunisia, 59% KSA). Expatriate internet users in Qatar are also much more likely to use Facebook than Qatari nationals—by 40 percentage points (23% Nationals vs. 65% Arab expats, 80% Asian expats, 65% Western expats, among internet users).

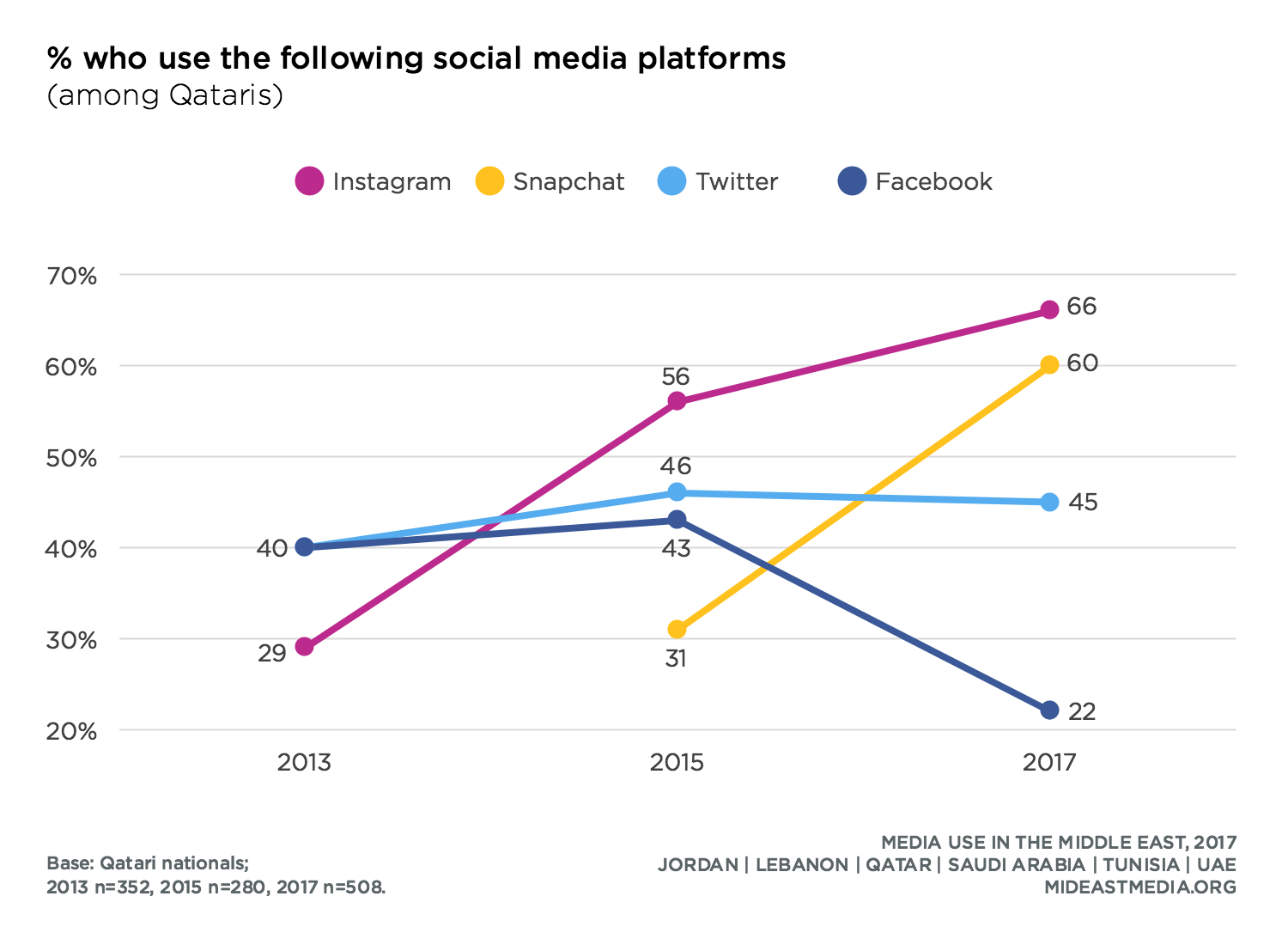

Such low Facebook penetration among Qatari internet users reflects a significant and steady drop over time (65% in 2013 vs. 53% in 2015 vs. 23% in 2017). Other countries in this study have experienced a more modest decline in Facebook penetration since 2013.

Use of YouTube has also dropped among Qatari internet users, from 58% in 2015 to 39% in 2017, while remaining fairly stable across the region during the same period. Instagram use rose across the region since 2015, while remaining stable in Qatar. Still, more Qataris use Instagram by a wide margin (at least 27 percentage points) compared with all other nationals except Emiratis, who use Instagram at roughly the same rate. Compared with expatriates in Qatar, Qatari nationals are less likely to use YouTube but more likely to use Instagram (YouTube: 39% Nationals vs. 52% Arab expats, 73% Asian expats, 65% Western expats; Instagram: 70% Nationals vs. 44% Arab expats, 35% Asian expats, 45% Western expats, among internet users).

Snapchat has increased in popularity in all countries since 2015, but Qataris are still far more likely to use Snapchat than internet users from any other country (64% Qatar vs. 51% KSA, 51% UAE, 20% Lebanon, 16% Jordan, 7% Tunisia). Qatari nationals are also more likely to use Snapchat compared with expatriates in the country by a wide margin (Snapchat: 64% Nationals vs. 27% Arab expats, 25% Asian expats, 36% Western expats, among internet users).

All Qataris use direct messaging (99%). Qataris estimate that about two-thirds of their direct messaging is with individuals and only one-third is through a group chat, which is the lowest percent of group messaging across the region (group messages: 33% Qataris vs. 52% other nationals). Most Qataris belong to group chats with friends and family, similar to other nationals (Qatar: 83% friends, 86% family). Yet Qataris are less likely than other nationals—and expatriates in their country—to belong to direct messaging groups with people who have similar interests and hobbies (29% Qataris vs. 51% other nationals; in Qatar: 29% Nationals, 39% Arab expats, 41% Asian expats, 36% Western expats).

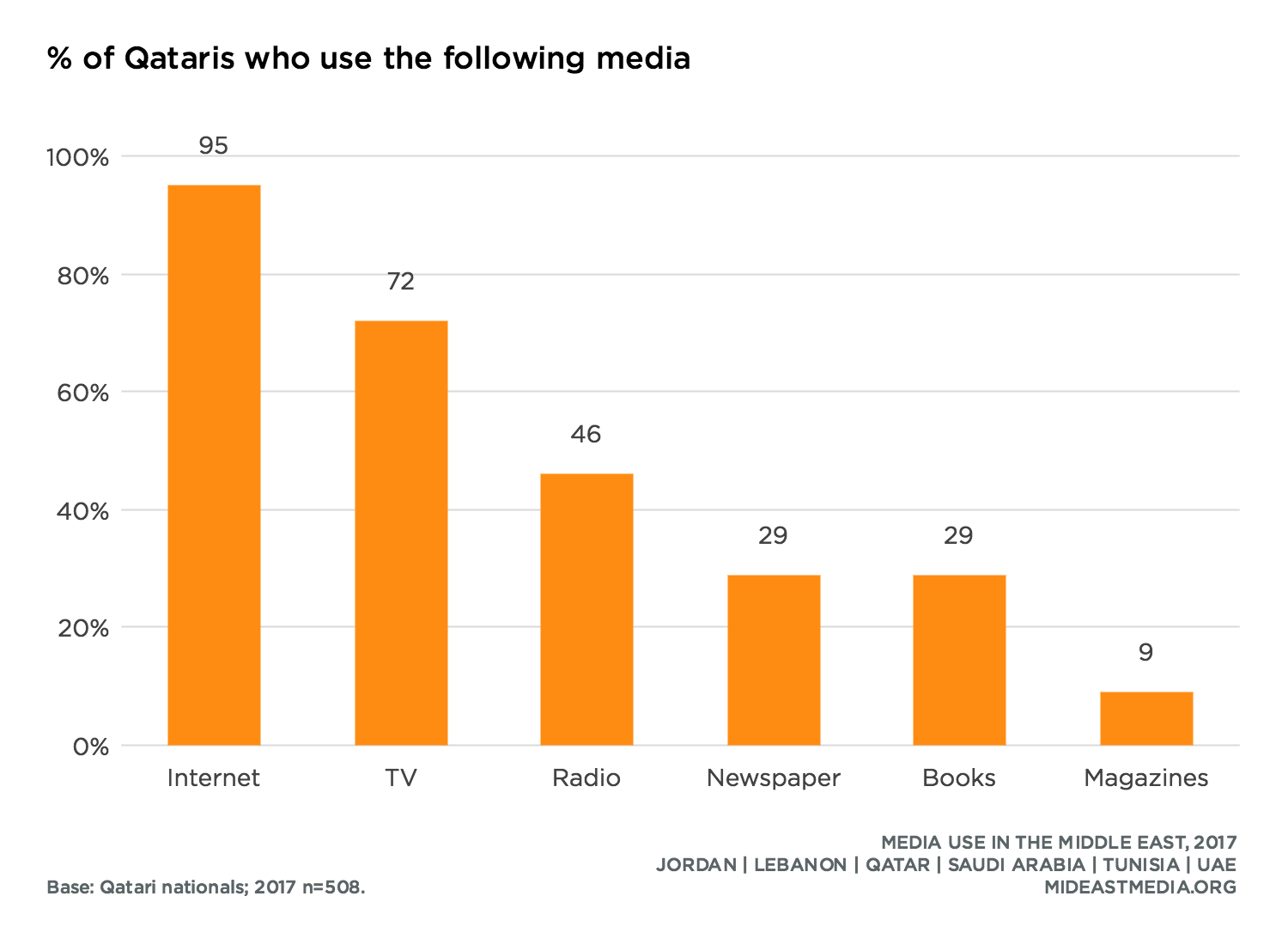

Internet penetration has risen over time and nearly all Qataris are now online (95% in 2017 vs. 85% in 2013). While internet use is lower among older Qataris—similar to other countries surveyed—eight in 10 of the oldest age group use the internet (96% 18-24 year-olds, 100% 25-34 year-olds, 97% 35-44 year-olds, 82% 45+ year-olds).

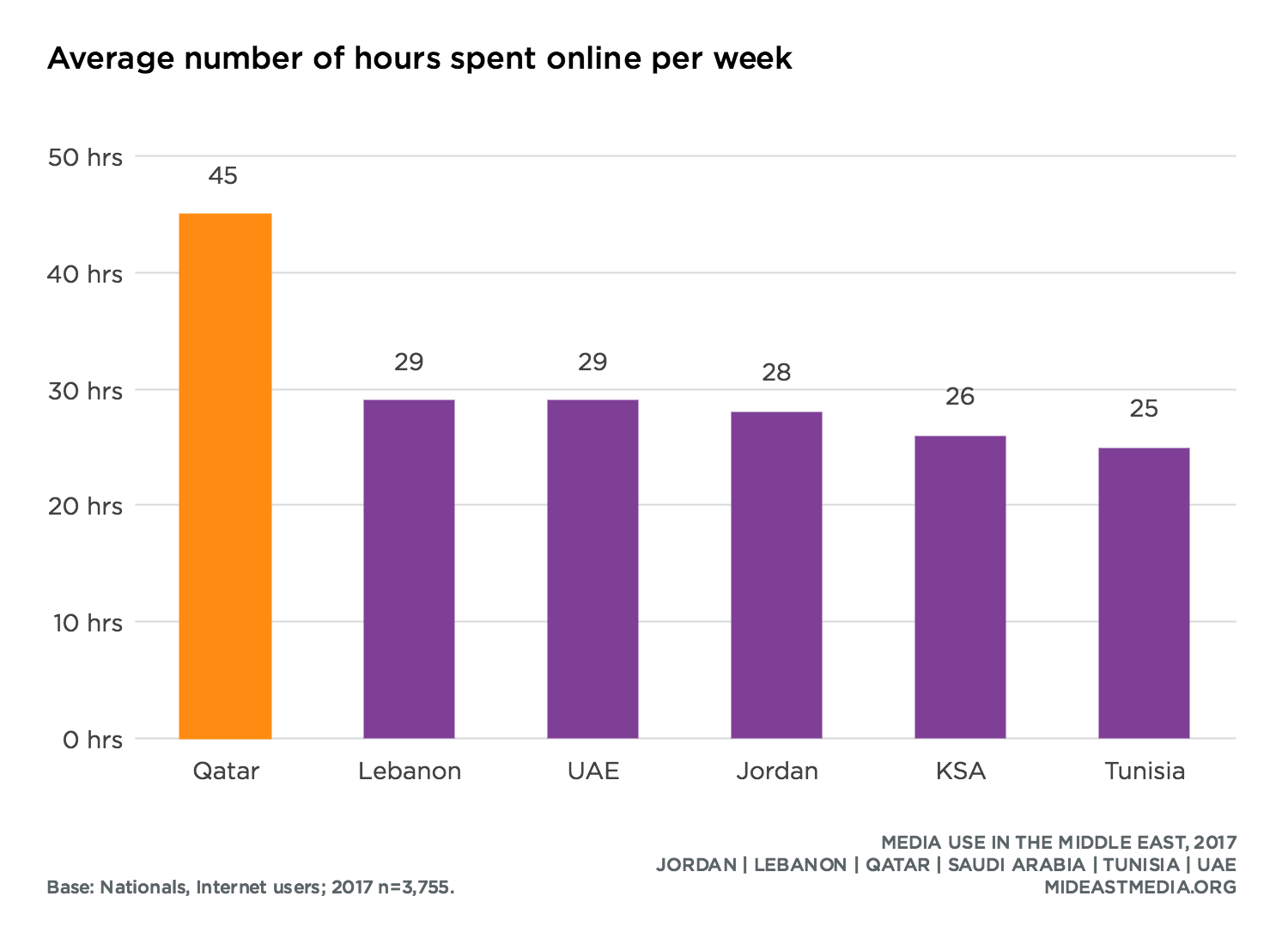

Not only are most Qataris online, they also spend a lot of time on the internet. Qataris estimate they spend an average of 45 hours per week on the internet compared with just 27 hours among other nationals. They also spend more time online than foreign nationals who live in Qatar (45 hours Nationals vs. 46 Arab expats, 41 Asian expats, 30 Western expats).

Almost all Qataris own a smartphone, more than in 2015 (94% in 2017 vs. 90% in 2015). In comparison, computer use has declined, and now fewer than half of Qataris say they connect to the internet with a computer (53% in 2015 vs. 45% in 2017). Computer use has similarly declined in all countries except Tunisia. Use of tablets also declined in Qatar, while tablet use increased or remained stable in all other countries except the UAE (Qatar: 18% in 2017 vs. 34% in 2015).

Wi-Fi and mobile data service connections are both very common in Qatar. In comparison, Saudis and Emiratis are much more likely to connect via Wi-Fi than through a mobile data service, while the opposite is true for Jordanians (Qatar: 87% Wi-Fi vs. 78% data service; KSA: 84% Wi-Fi vs. 55% data service; UAE: 97% Wi-Fi vs. 58% data service; Jordan: 40% Wi-Fi vs. 84% data service).

Qataris, along with Emiratis, spend the most time socializing with family face-to-face each week (45 hours Qatar, 45 UAE vs. 35 Jordan, 33 Lebanon, 28 KSA, 27 Tunisia). Similar to other nationals, Qataris spend far less time—13 hours per week—socializing with friends face-to-face.

Qataris spend twice as much time socializing online with friends as with family (7 hours with family vs 14 hours with friends). Other nationals, however, spend a roughly equal number of hours socializing online with family and friends.

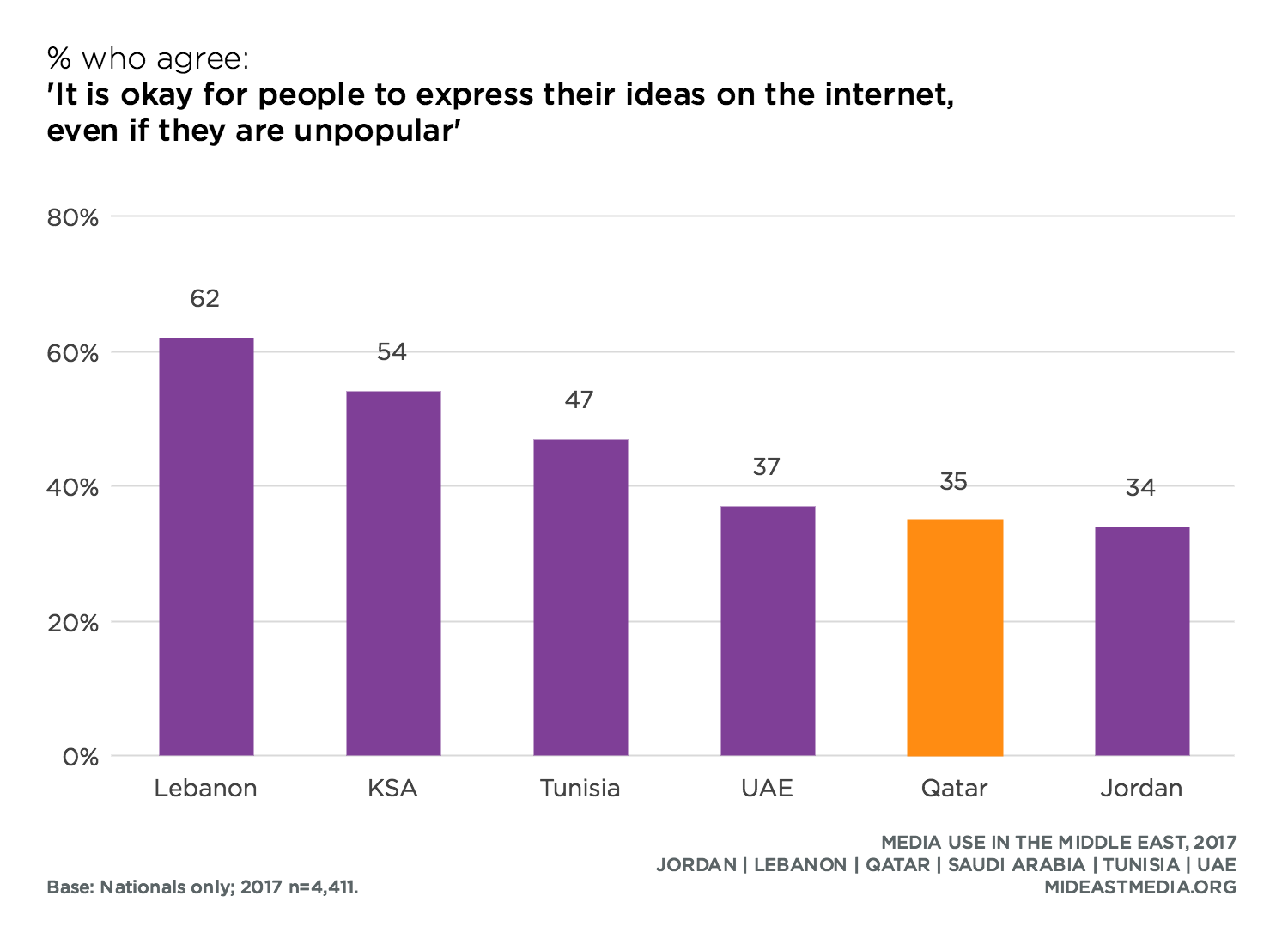

Qataris, along with Emiratis and Jordanians, are less likely than other nationals to say that it is okay for people to express unpopular ideas on the internet. Only one-third of Qataris, Emiratis, and Jordanians support such freedom of speech online.

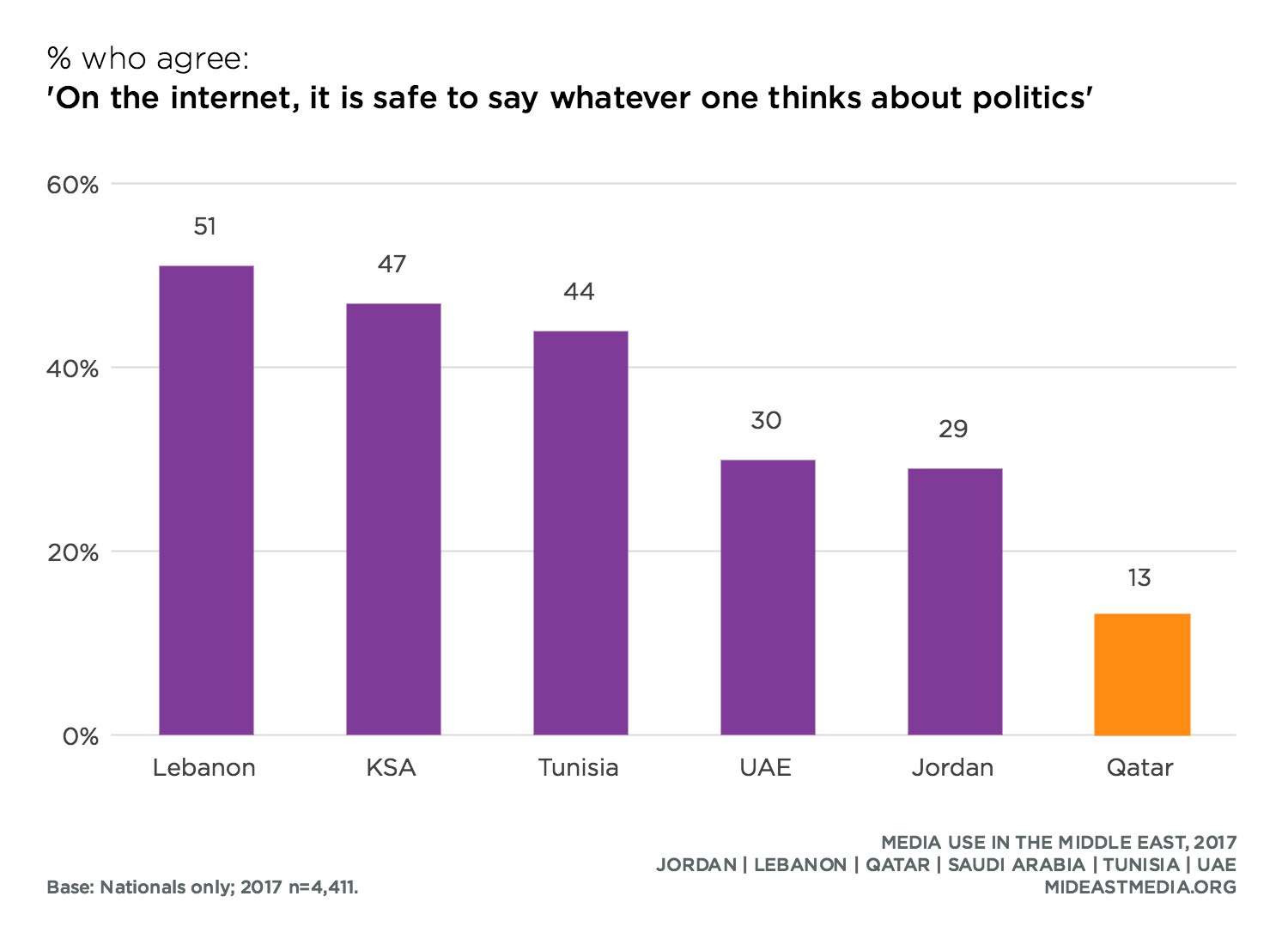

Further, Qataris are much less likely than other nationals to say people should be able to criticize government online or that it is safe to say whatever one thinks about politics online (criticize governments: 18% Qataris vs. 48% other nationals; safe to talk about politics online: 13% Qataris vs. 42% other nationals). They are also less likely than expatriates in Qatar to agree with these statements (criticize governments: 18% Nationals vs. 34% Arab expats, 36% Asian expats, 27% Western expats; safe to talk about politics online: 13% Nationals vs. 26% Arab expats, 30% Asian expats, 21% Western expats).

Qataris are also less likely than other nationals—and expatriates in their country (especially Asian and Western expats)—to feel comfortable saying what they think about politics in general (23% Qataris vs. 44% other nationals; in Qatar: 23% Nationals vs. 28% Arab expats, 43% Asian expats, 49% Western expats).

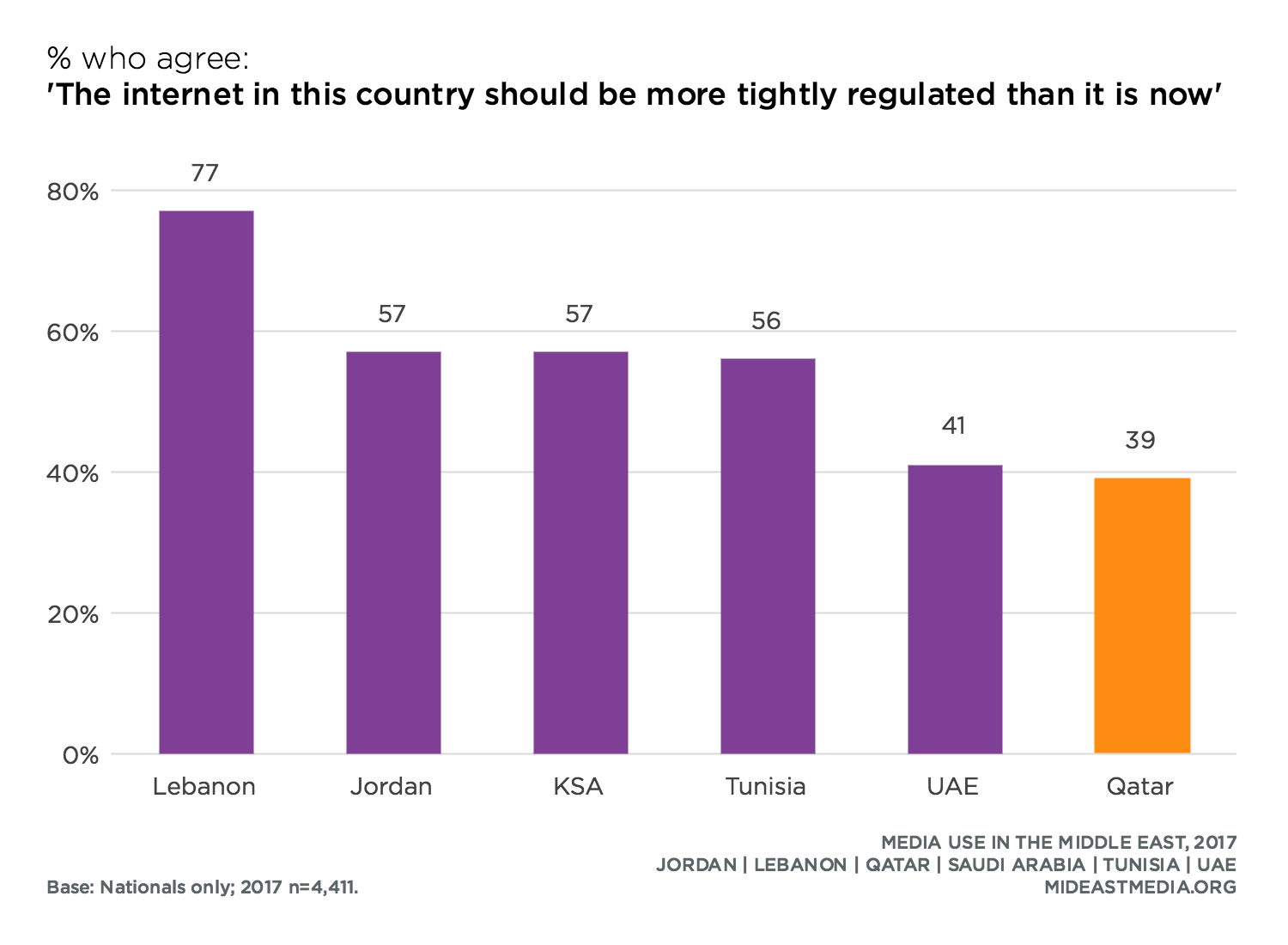

Qataris are less likely than other nationals in this study to support more internet regulation—by 22 percentage points (39% Qataris vs. 61% other nationals). This represents a nearly 30 percentage point decrease in support of internet regulation in Qatar over the past two years—the only decrease in the region (67% in 2015 vs. 39% in 2017).

Qatari nationals report a similar level of support for regulation as expatriates in their country (support more regulation: 39% Nationals vs. 33% Arab expats, 36% Asian expats, 33% Western expats).

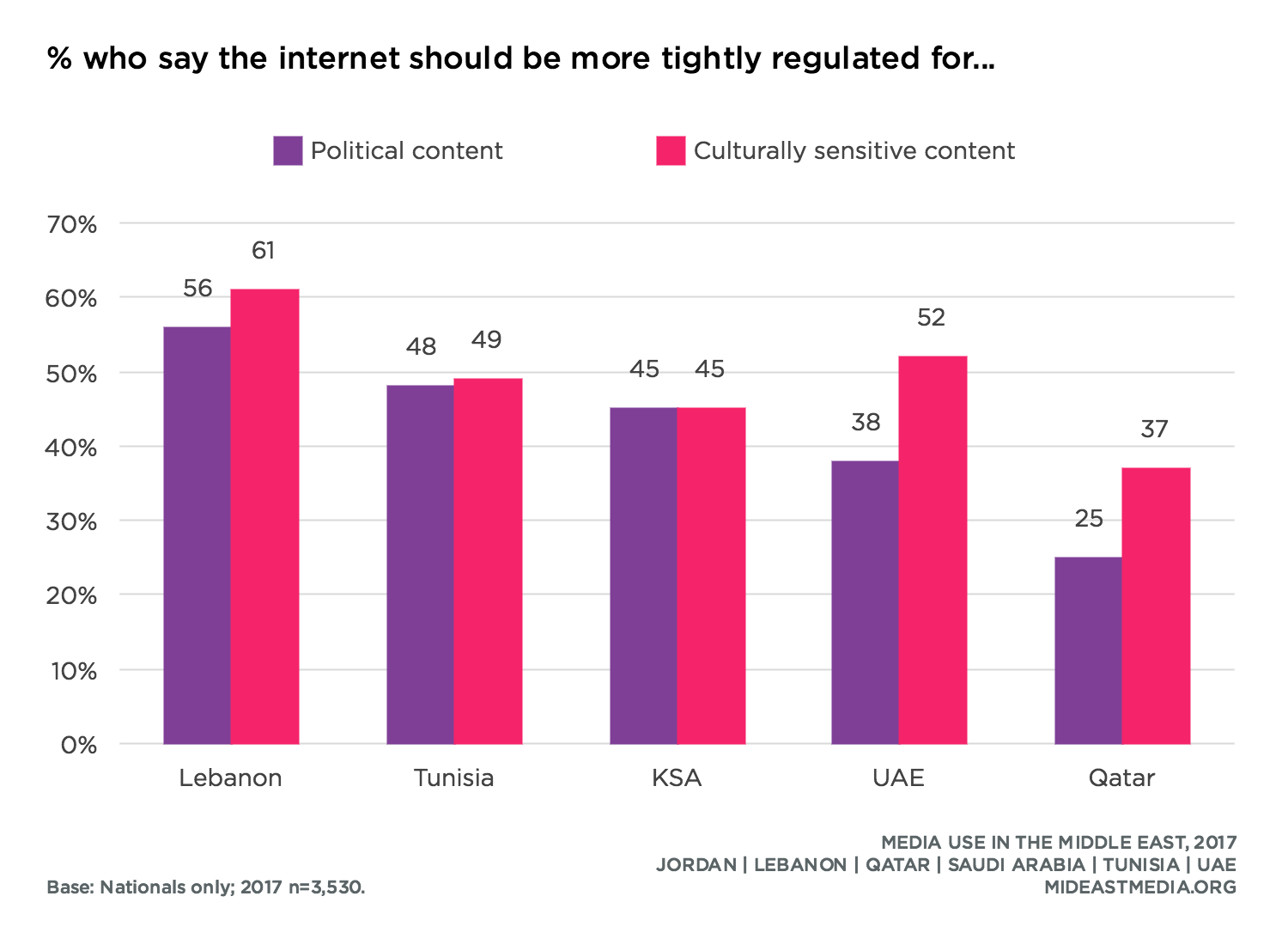

Compared with other nationals, supporting internet regulation related to political and culturally sensitive content is less popular among Qataris, while favoring tighter regulation concerning user privacy and keeping the internet affordable is similar to other nationals surveyed (political content: 25% Qataris vs. 49% other nationals; culturally sensitive content: 37% Qataris vs. 52% other nationals; user privacy: 53% Qataris vs. 58% other nationals; affordability: 54% Qataris vs. 54% other nationals).

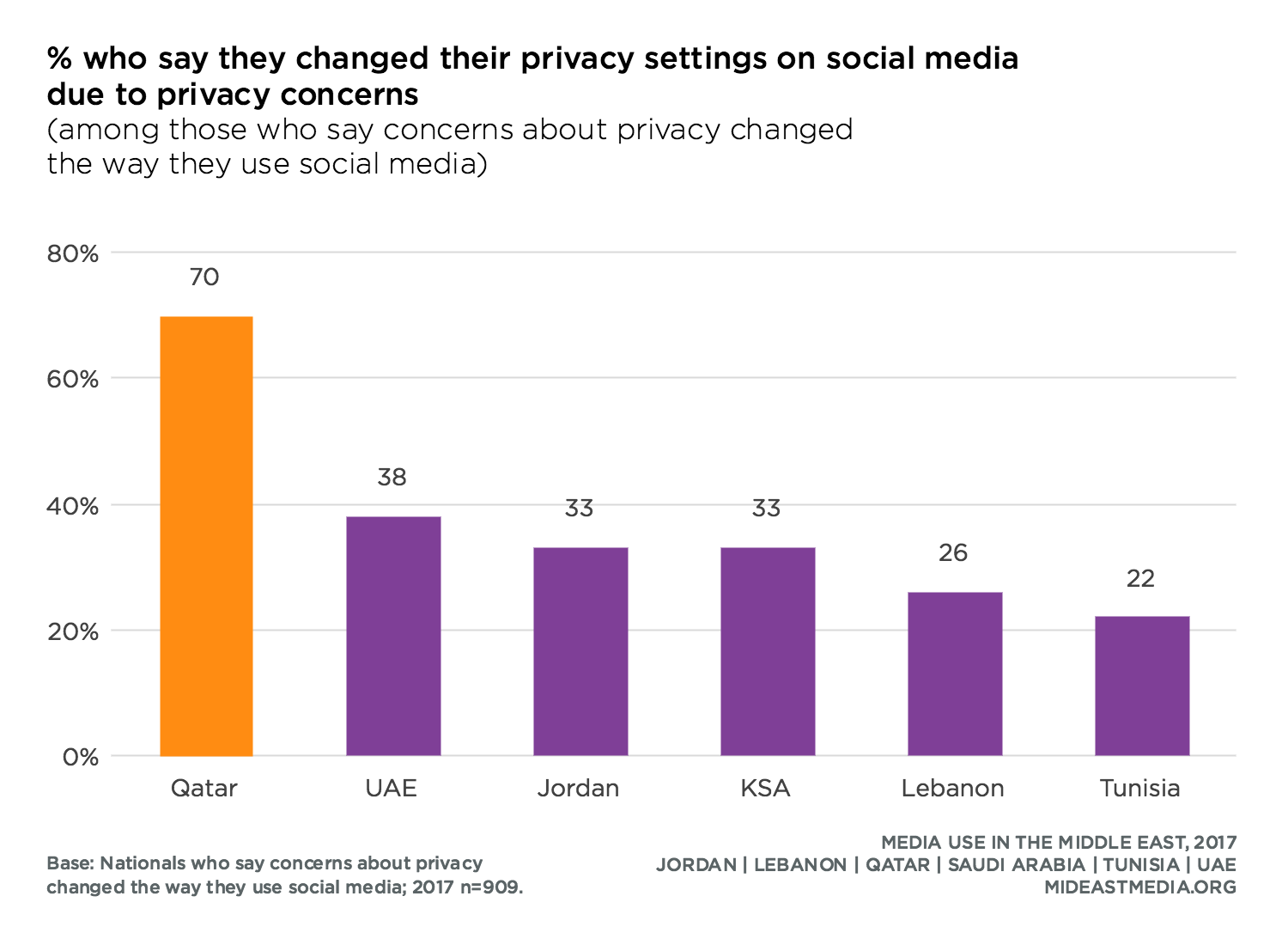

On average, 20% of Arab nationals say that concerns about privacy changed the way they use social media, and Qataris are right at the average (21%). Of those who changed their social media behavior due to privacy concerns, Qataris are far likelier than other nationals to have changed their privacy settings.

Perhaps because of this, Qataris are only half as likely as other nationals to express concern about companies checking what they do online and three time less likely to worry about governments checking their online activity (companies checking: 20% Qataris vs. 40% other nationals; governments checking: 12% Qataris vs. 37% other nationals). Qataris are also less likely to be worried about online surveillance compared to expatriates living in Qatar (companies checking: 20% Nationals vs. 28% Arab expats, 37% Asian expats, 24% Western expats; governments checking: 12% Nationals vs. 22% Arab expats, 38% Asian expats, 31% Western expats).

Qatar is the only country where a majority of nationals feel international news organizations’ coverage of their country is fair (60% Qataris vs. 35% other nationals). Respondents were asked if they thought international news outlets’ coverage is fair, biased against, or biased in favor of their own country, the Arab world outside their country, and the Western world. Most Qataris feel international news organizations’ coverage of Qatar is fair, with few believing it is biased against the country (news about own country: 60% fair, 13% biased against).

The pattern is similar regarding Qataris’ perceptions of international news outlets’ coverage of the rest of the Arab world. Qataris are the most likely to feel coverage is fair and the only country where more than half feel coverage is fair (54% Qataris vs. 33% other nationals).

With regards to news about the Western world, Qataris are again the nationals most likely to say coverage is fair (51% Qataris vs. 31% other nationals). However, unlike their perceptions of coverage about Qatar and other Arab countries, Qataris are much more likely to say news is biased in favor of the Western world than against it (25% biased in favor vs. 3% biased against).

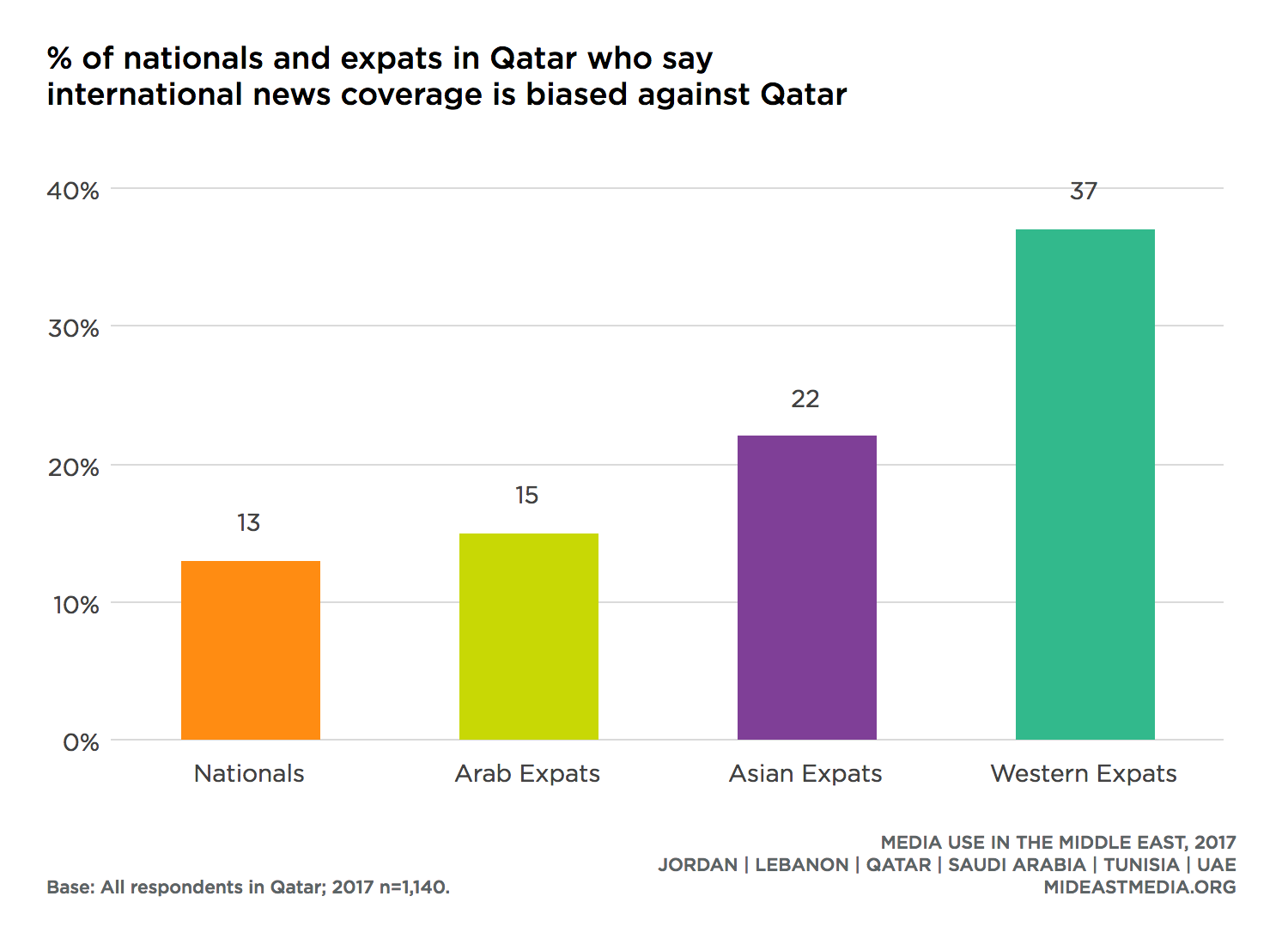

Western expatriates living in Qatar are much more likely than Qataris and Arab expatriates living in Qatar to say that news coverage is biased against Qatar (37% Western expats vs. 13% Nationals, 15% Arab expats, 22% Asian expats). Qatari nationals hold a very different opinion than Western expatriates about coverage of the West; few Qataris feel coverage is biased against the Western world, compared with nearly four in 10 Western expatriates who believe there is a negative bias against the Western world (3% Nationals vs. 38% Western expats).

In general, Qataris and Arab expatriates hold similar views about international news bias. One notable difference, however, is that Arab expatriates are almost twice as likely as Qatari nationals to feel international news coverage is biased against the Arab world outside Qatar (34% Arab expats vs. 18% Nationals).

Two-thirds of Qataris get news on their phone, a rate lower than nationals from all other countries except Tunisia (67% Qatar, 62% Tunisia vs. 77% Jordan, 76% Lebanon, 94% KSA, 98% UAE).

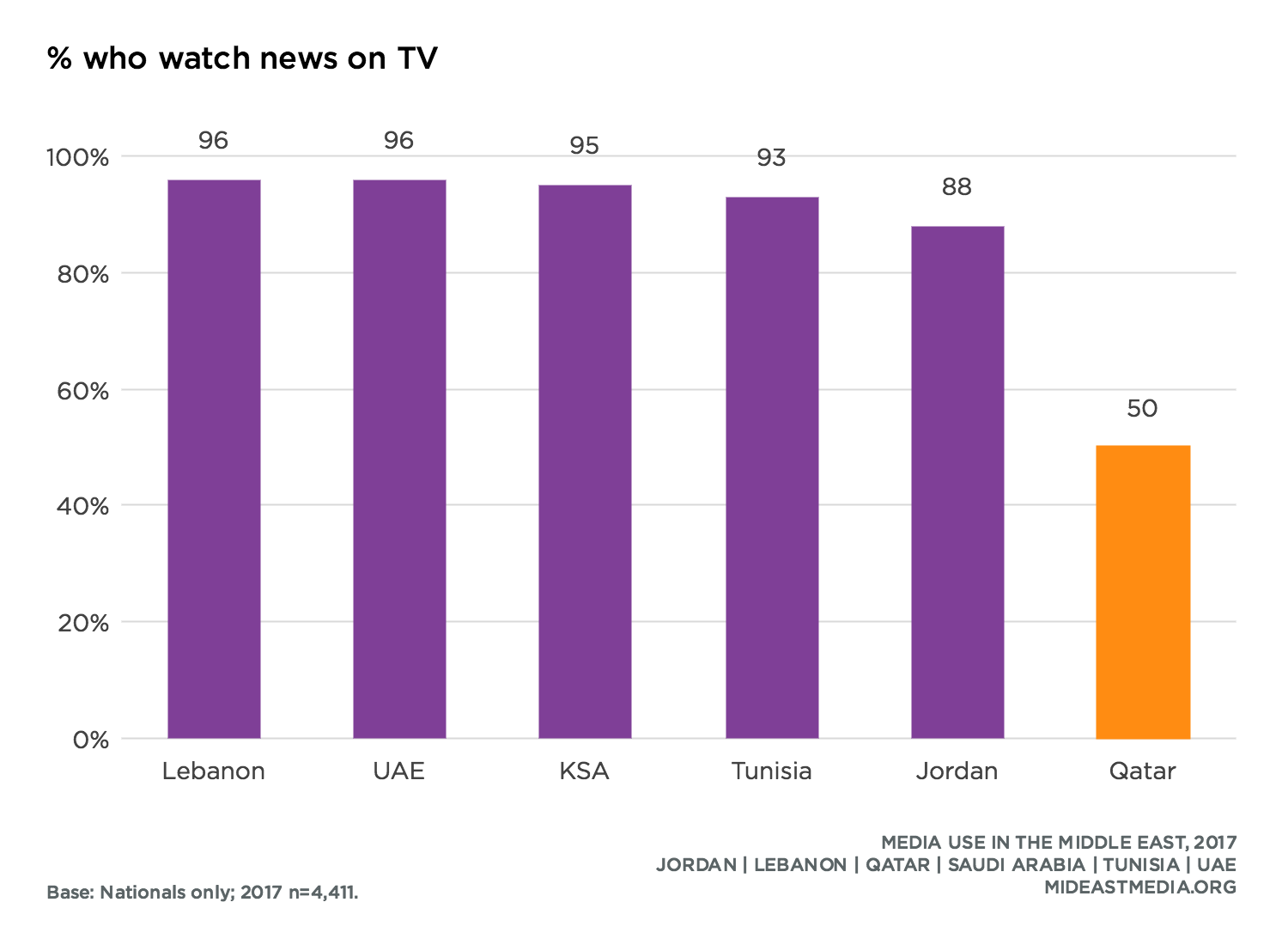

Qataris are also much less likely to get news from TV compared with other nationals. Only half of Qataris say they get news from TV compared to nearly all other nationals (50% Qataris vs. 93% other nationals).

When asked for the locale of their favorite news organization, about half of Qataris said their favorite outlet is based in Qatar, while most of the remainder either did not know or declined to say (53% based in Qatar vs. 33% don’t know or declined). When asked about ownership, one-third of Qataris said their favorite news organization is state/government owned, a quarter said it is privately owned, and four in 10 did not know or did not say (33% state/government owned, 25% private/corporate ownership, 41% do not know/declined).

Similar to other nationals, two-thirds or more of Qataris watch news and comedy videos on TV and online. Qataris, though, are the most likely nationals to watch religious and spiritual videos through either platform (online: 63% Qatar vs. 58% Jordan, 56% KSA, 56% UAE, 37% Tunisia, 29% Lebanon; on TV: 68% Qatar vs. 62% Jordan, 65% KSA, 60% UAE, 47% Tunisia, 40% Lebanon).